Last November, Democrats defied political gravity and expanded their razor-thin majority in the U.S. Senate, enabling them to continue confirming judicial nominees for another two years. Six months into their Senate, it is worth taking a look at their progress and the landscape that remains.

In the last Congress, despite depending on the Vice President’s vote for their Senate majority, the Senate confirmed 97 Article III judges: one to the U.S. Supreme Court; 28 to the Courts of Appeal; and 68 to the U.S. District Courts. To maintain a similar pace, Democrats would need to have confirmed between 25-30 judges so far.

The good news is that, so far, Democrats are on pace to slightly exceed their pace, having confirmed 39 judges so far (7 appellate and 32 district) and on pace to confirm two more next week. The less positive news, however, is that the pace of nominations from the White House has dramatically slowed. After sending 55 nominations to the Senate in his first year and 70 in his second year, Biden has nominated just 30 judges so far this year. He has also had to deal with the first nomination losses of his Administration, with one appellate and two district judges being withdrawn, with a third potentially going the same route.

As a result of this slowdown in nominations, the majority of existing judicial vacancies lack nominees, and the Senate has only enough nominees to carry through its current confirmation pace to August. A summary of this landscape follows:

D.C. Circuit – 0 vacancies out of 11 judgeships

In two and a half years, Biden has managed to appoint four judges to the so-called “second highest court in the land”, starting with now-Supreme Court Justice Jackson, who was confirmed to the court in June 2021, a mere two months after her nomination. In 2022, Judge David Tatel was replaced by Judge Michelle Childs while Judge Florence Pan was confirmed to replace Jackson when she was elevated. This year, 37-year-old Brad Garcia was confirmed to fill the last remaining vacancy on the court, vacated lat year by Judge Judith Ann Wilson Rogers. The influential court has only one judge who is currently eligible for senior status, 78-year-old Karen Henderson, who has shown no sign of slowing down, making it unlikely that Biden would have any more appointees to the court this term.

The only district court that reports to the D.C. Circuit is the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. The 15-judgeship court has two sitting Biden appointees and two current vacancies, from Pan’s elevation, for which Judge Todd Edelman remains pending on the senate floor for confirmation, and from Judge Amy Berman Jackson’s move to senior status last month, for which D.C. Court of Appeals Judge Loren AliKhan is pending a final Judiciary Committee vote. The outgoing chief judge of the court, Judge Beryl Howell, is the sole appointee on the court who is eligible for senior status, leaving the possibility that Biden may get an additional appointment to the court.

First Circuit – 1 vacancy out of 6 judgeships (no nominee pending)

The smallest court of appeals in the country was also the sole geographically-based court not to see a single Trump appointment. Biden has already named Judge Gustavo Gelpi and Public Defender Lara Montecalvo to the court. This year, reproductive rights attorney Julie Rikelman was confirmed to replace Judge Sandra Lynch, moving the court significantly to the left. The final seat, based in New Hampshire, was vacated by Judge Jeffrey Howard last year, and lacks a nominee now that Michael Delaney withdrew last month in the face of bipartisan opposition. Unless the Biden Administration has been pre-vetting an alternate candidate, it is unlikely that a new nominee to replace Howard will hit the senate before August. Meanwhile, Judge William Kayatta, who is based out of Maine, remains a possible contender to take senior status as well, giving Biden a chance to name five out of the six judges on the court.

While this Senate has already confirmed district judges to seats in Massachusetts and Puerto Rico, the district courts covered by the First Circuit have two pending judicial vacancies, both in Massachusetts, and both have nominees pending a final vote on the floor.

An additional five district judges in the circuit remain eligible for senior status: Chief Judge F. Dennis Saylor and Judges Nathaniel Gorton, Patti Saris, and Richard Stearns in Massachusetts; and Judge Aida Delgado-Colon in Puerto Rico. Judge Jon Levy, who becomes eligible for senior status next year in Maine, has already announced his intention to take it. No public process has been announced to select a replacement.

Second Circuit – 0 vacancies out of 13 judgeships

After replacing five left-leaning judges on the Second Circuit in the last Congress, the Senate confirmed Justice Maria Araujo Kahn to replace 81-year-old conservative Jose Cabranes in March, transforming the court. With Chief Judge Debra Ann Livingston unlikely to take senior status before her term as chief ends, there is unlikely to be another appointment to the Second Circuit for several years.

Of the states covered by the Second Circuit, Connecticut, which saw three Biden appointees hit the bench last year, currently has two of the eight active district judgeships vacant and one pending nominee, Judge Vernon Oliver, who received a Judiciary Committee hearing last month. It is expected that a second nominee is incoming.

Meanwhile, the district courts in New York, after six confirmations this Congress, are down to four current and future vacancies. The Eastern District of New York has one vacancy out of sixteen judgeships, with a nominee pending on the floor. Additionally, one nominee, Margaret Garnett, was submitted this week to fill a vacancy on the Southern District of New York. The remaining two vacancies, one on the Southern District, and one on the Western District, lack nominees.

Third Circuit – 1 vacancies out of 14 judgeships (no nominee pending)

The Senate confirmed two Biden appointees to this court last Congress (Arianna Freeman nominated to replace Judge Theodore McKee and Justice Tamika Montgomery-Reeves to replace Judge Thomas Ambro). This year, the Senate confirmed Cindy Chung to replace Judge Brooks Smith. This leaves one vacancy, left by Judge Joseph Greenaway’s retirement, which lacks a nominee, but is expected to get one expeditiously. Additional vacancies this Congress are unlikely unless Judge Kent Jordan chooses to take senior status.

All three states covered by the Third Circuit have judicial vacancies. The biggest number are in Pennsylvania, which has three vacancies, two of which have nominees. Additionally, Judge Richard Andrews on the District of Delaware has indicated his desire to take senior status in December and Judge Jennifer Hall is being nominated to replace him.

The District of New Jersey, vacancy-ridden when the Biden Administration came to office, is now down to two seats left to fill, both of which are scheduled to open in the coming months. An additional seat may open if Biden chooses to elevate a district court judge to replace Greenaway (if he does so, Judges Georgette Castner and Zahid Quraishi are the most likely). The Senate previously confirmed two judges to the court this Congress and will likely process new nominees promptly.

Fourth Circuit – 1 vacancy out of 15 judgeships (no nominee pending)

After the confirmation of Judge DeAndrea Benjamin to the Fourth Circuit early this year, the big question mark in the Fourth Circuit is a Maryland vacancy first announced in December 2021 that still lacks a nominee. This has been reported to be the result of an impasse between the White House and Sen. Ben Cardin. With this Congress six months through, the clock is ticking for the two sides to reach a compromise, particularly as additional vacancies on the Fourth Circuit are possible with six other judges eligible for senior status (Chief Judge Roger Gregory, who ends his term as chief this year, is one judge to watch in particular).

One sign of optimism for the White House is that they were able to agree on two district court nominations in Maryland that are pending before the Senate, including Judge Brendan Hurson on the senate floor.

The Western District of North Carolina, meanwhile, has one current and one future vacancy, with no nominee on the horizon. An additional three North Carolina judges are eligible for senior status, leaving the possibility of additional vacancies opening.

The District of South Carolina currently has one vacancy, after Judge J. Michelle Childs was elevated to the D.C. Circuit. Late last year, it was suggested that U.S. Magistrate Judge Jacqueline Austin and attorney Beth Drake were under consideration to replace Childs, but no nominee has hit the senate yet. Additional vacancies are possible as Judge David Norton was rumored to be considering senior status in 2021, and Judge Richard Gergel is eligible as well.

The confirmations of two Virginia district judges earlier this year has left the state without any vacancies. With Judge Leonie Brinkema on the Eastern District of Virginia showing little appetite for slowing down, it is unlikely that the White House would get additional appointments in this state this term.

Meanwhile, West Virginia is the only state in the Fourth Circuit that has not yet seen a vacancy under Biden. Nonetheless, four of the state’s eight active judges are eligible for senior status, making it a reasonable chance that an additional vacancy may open this Congress.

Fifth Circuit – 1 vacancy out of 17 judgeships (one nominee pending)

Having appointed Judge Dana Douglas to the Fifth Circuit last year, Biden is poised to have a second appointment to the court in Judge Irma Ramirez. Six other judges on the Fifth Circuit are eligible for senior status, leaving a serious possibility that additional vacancies may open before the end of this Senate.

Louisiana’s Republican senators have managed to reach consensus with the Biden Administration on four nominations now, including two pending district court picks. It also appears that the senators had signed off on a third district court nominee to fill the last vacancy on the district court but the White House decided to drop the nominee from the package. Nonetheless, the good relationship that the parties have built should stand them well in filling the vacancy, as well as others that may open (six other Louisiana judges are eligible for senior status and a seventh will become eligible next year).

Mississippi, meanwhile, is in a holding pattern as the nomination of Scott Colom has stalled due to the late-breaking opposition of Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith. With two other judges eligible for senior status, it is possible that a deal may grease Colom’s path to confirmation. Otherwise, only a change in blue slip policy would allow him to move forward.

No other state has more pending district court vacancies than Texas (eight to be precise) without any nominees pending. However, Texas senators have been collecting applications for the vacancies and the successful collaboration over Ramirez’s nomination suggests that deals can still be made. With twelve additional judges eligible for senior status, more vacancies may be on the horizon.

Sixth Circuit – 1 vacancies out of 16 judgeships (one nominee pending)

Of the three vacancies on the Sixth Circuit that opened in the Biden Administration, only the Ohio based seat of Judge R. Guy Cole remains open. Rachel Bloomekatz, nominated to replace Cole, is awaiting a final vote on the senate floor, which should come before the August recess. Of the remaining judges on the court, five are eligible for senior status: Judges Karen Nelson Moore, Eric Clay, Julia Smith Gibbons, Richard Allen Griffin, and Jane Branstetter Stranch. As such, it would not be surprising to see an additional vacancy open before the end of this Congress.

On the district court level, two of the four states under the Sixth Circuit have vacancies pending. After the White House’s proposal to nominate conservative lawyer Chad Meredith to the Eastern District of Kentucky fell through, Judge Karen Caldwell withdrew her intention to take senior status. As Caldwell and Judge Danny Reeves are the only judges on the Kentucky federal bench who are eligible for senior status, it is unlikely that Biden would be able to name any judges to the state.

With the confirmation of Judge Jonathan Grey to the Eastern District of Michigan this year, the court has three pending vacancies with two nominees pending before the Senate Judiciary Committee. With five other Michigan district judges eligible for senior status, there is a strong possibility that additional vacancies may open this Congress.

After the confirmation of four judges last year, there are no vacancies on the district courts of Ohio. However, five judges remain eligible for senior status, and it is conceivable that additional vacancies may open, particularly as Chief Judge Algernon Marbley ages out of his position next year.

Finally, a vacancy is pending on the Western District of Tennessee. The White House and Tennessee Senators battled over the Sixth Circuit nomination of Andre Mathis, and no nominee has been put forward to replace Judge John Fowlkes, who took senior status last year. If additional vacancies open (three judges are eligible for senior status), it is possible that the White House may be able to strike a package deal with Tennessee senators to fill the vacancies.

Seventh Circuit – 1 vacancy out of 11 judgeships (no nominees pending)

Having named Judge Candace Jackson-Akiwumi, Judge John Lee, and Judge Doris Pryor to the Seventh Circuit last Congress, a fourth vacancy, opened by Judge Michael Kanne’s death, still lacks a nominee. Indiana’s Republican Senators worked with the White House to support Pryor, Judge Matthew Brookman for a district court seat, and two U.S. Attorney nominees. As such, it is expected that the White House will put forward a compromise candidate for the Seventh Circuit, likely paired with candidates to fill two vacancies on the Northern District of Indiana. If an additional seat opens, it will likely be that of Judge Ilana Rovner, who is in her mid-eighties and has been on the bench since the 1970s.

On the district court level, two vacancies are pending on the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, with one nominee pending a final vote on the senate floor. The last vacancy will likely get a nominee in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, in Wisconsin, Judge William Pocan‘s nomination was withdrawn due to the opposition of Sen. Ron Johnson, and Wisconsin’s senators recommended two alternate candidates for the seat: state judge Marc Hammer and personal injury attorney Byron Conway three weeks ago. As such, a nominee is unlikely to come before September. However, with three other Wisconsin district judges eligible for senior status, another vacancy may well open before the end of the Congress.

Eighth Circuit – 0 vacancies out of 11 judgeships

The Eighth Circuit remains the sole court of appeals not to see a vacancy open under Biden, even as three judges are currently eligible for senior status and a fourth becomes eligible next year. Each of the four, however, are fairly conservative, and may choose to hold off on senior status until a Republican Administration.

Out of the eight active judgeships among Arkansas’ two districts, only one remains vacant, left open by Judge P.K. Holmes’ move to senior status in 2021. However, despite two and a half years since Judge Holmes announced his move to senior status, no nominee has been announced. Given that the White House has been unable to agree with senators even on U.S. Attorney nominees in Arkansas, the prospects of a nominee seem remote, despite talks ongoing.

With the confirmation of Judge Stephen Locher to the Southern District of Iowa last year, the state is unlikely to see further vacancies this Congress, given the youth of all of its judges.

Having named two judges to the Minnesota district court last Congress, Biden has opportunity to replace Judge John Tunheim this year, and is expected to nominate Minnesota Court of Appeals Judge Jeffrey Bryan next month.

With three vacancies, Missouri is likely the sight of much Democratic frustration, as the state’s Republican senators have shown little willingness to agree to confirm replacements. As such, barring a change in blue slip policy, it is unlikely that Missouri will get any new judges soon.

The District of Nebraska has had a vacancy pending from Judge John Gerrard’s move to senior status. Senator Deborah Fischer opened the application process to replace Gerrard with a deadline in December 2022, suggesting that recommendations have likely already been made to the White House. If the Administration and senators can get on the same page, a nomination can likely be made and confirmed this year.

The District of North Dakota has two Trump appointees and no vacancies, while its neighbor to the south has two vacancies that need filling. Recent press suggests that the state’s Republican senators are not standing in the way of new appointments and that conversations are ongoing, suggesting optimism that nominations can be confirmed by the end of the year.

Ninth Circuit – 1 vacancy out of 29 judgeships (one nominee pending)

Compared to other courts of appeals, the White House has had comparative success in confirming judges to the Ninth Circuit, naming seven, with an eighth, Judge Ana de Alba, pending a final Senate vote. Of the judges who remain, six judges remain eligible for senior status, raising a fair possibility that an additional appointment may come Biden’s way.

Of the district courts covered by the Ninth Circuit, Biden has already named 29 judges, with seven additional nominees pending. One state that is still awaiting a nominee, however, is Alaska, which has still not seen a nominee to replace Judge Timothy Burgess who took senior status in December 2021. With Judge Sharon Gleason becoming eligible for senior status next year, a nomination grows increasingly important.

Similarly, Arizona has not seen any Biden district court appointees, although that is because no seat has opened during the Administration. However, in 2024, judges Douglas Rayes and James Soto become eligible for senior status, raising the possibility that Biden may be able to name some judges in Arizona.

California is the site of Biden’s greatest success on judicial nominations, with Biden having named 19 district judges, more than any other president in one term. An additional four nominees are pending confirmation of the senate floor and expected to be confirmed in the next few weeks. Furthermore, three other vacancies still lack nominees, and additional twelve judges are eligible for senior status. As such it would not be surprising to see Biden named thirty judges to the California district courts by the end of this term.

The District of Hawaii is expected to have some new judges with Judges J. Michael Seabright and Leslie Kobayashi taking senior status next year. Hawaii Senators Mazie Hirono and Brian Schatz have set up an evaluation committee to review applications with a deadline in March 2023, making it likely that new nominees should hit the senate in the coming months.

This Senate confirmed Judge Amanda Brailsford unanimously to a seat on the District of Idaho, adding gender diversity to one of a handful of all-male courts left in the nation.

Judge Dana Christensen in Montana has announced his intention to take senior status upon confirmation of a successor, and Montana’s senators have set up an application process to replace him with an application deadline on June 14 of this year. If the senators can reach an agreement on a nominee, confirmation can be expected promptly.

Having confirmed two judges to the District of Nevada last year, no additional vacancies are expected this Congress, with the bench largely composed of fairly young Obama and Biden nominees.

After the confirmation of Justice Adrienne Nelson to the District of Oregon earlier this year, the state is primed for two more Biden nominees, to replace Judges Ann Aiken and Marco Hernandez. Moving quickly, Oregon senators have already recommended six candidates rates to replace Hernandez. While Aiken does not base her chambers out of Portland, it is possible that one of the recommended candidates may be chosen to replace her.

The Eastern and Western Districts of Washington have seen a major transformation under Biden, with him filling six out of eleven judgeships already. An additional two nominees are expected to be confirmed in July, with the nomination of Charnelle Bjelkengren to the last remaining vacancy likely being a closer call.

Tenth Circuit – 1 vacancy out of 12 judgeships (no nominee pending)

The Kansas seat vacated by Judge Mary Briscoe is the oldest appellate vacancy in the country, and the site of failure by the White House when their first nominee, Jabari Wamble, crashed and burned due to the expectation of a bad ABA rating. Since then, there is little peep regarding a new Tenth Circuit nominee. Meanwhile, three other judges are also eligible for senior status, leaving the possibility that an additional appointment to the court may come Biden’s way.

The Colorado federal bench has seen significant turnover under Biden, with four out of the state’s seven judgeships filled with Biden appointees. Biden has a good chance to secure a fifth appointment upon the confirmation of Judge Kato Crews to fill the lone vacancy on the district court. Meanwhile, Judge Philip Brimmer becomes eligible for senior status next year, raising the possibility of a sixth appointment.

The District of Kansas has one pending vacancy, opened last year by Judge Julie Robinson’s move to senior status. The White House previously nominated Jabari Wamble to this seat, but Wamble withdrew in the face of an unfavorable ABA review, leaving the White House back at square one. If this seat gets filled now, it will likely be in conjunction with the Tenth Circuit vacancy.

Having confirmed three judges to the District of New Mexico, the court now has no pending vacancies, and is unlikely to have additional ones this Congress.

There are currently two vacancies on the Oklahoma district courts, and while Senators James Lankford indicated that he and the White House were having productive conversations back in 2021, there has been no nominee submitted and no updates since Sen. Markwayne Mullin replaced Sen. James Inhofe.

The District of Utah has a single vacancy, from Judge David Nuffer’s move to senior status last year. There has been little movement on a nominee publicly.

The District of Wyoming has a pending vacancy from Judge Nancy Freudenthal’s move to senior status last year. However, there appears to be little movement on a replacement and it is unclear what the status of negotiations is at.

Eleventh Circuit – 0 vacancies out of 12 judgeships

The Biden Administration achieved a significant victory last month when civil rights attorney Nancy Abudu was confirmed to the Eleventh Circuit. However, unless Judge Charles Wilson chooses to take senior status, the Administration is unlikely to secure a second appointment on the circuit.

On the district court level, Alabama has two pending vacancies, one from the elevation of Judge Andrew Brasher in the Trump Administration, and the second from Judge Abdul Kallon’s untimely resignation. Both lack nominees and it remains to be seen if a package can be reached (it’s possible that Alabama senators may demand the renomination of Trump nominee Edmund LaCour).

Florida currently has eight current and future district court vacancies, all of whom lack a nominee. Both Senator Marco Rubio and Florida’s Democratic House delegation recommended attorney Detra Shaw-Wilder (a Democrat) to the Southern District of Florida last year, but she was never nominated. However, in a breakthrough, the White House and senators were reported to have struck a deal to elevate two magistrate judges: Jacqueline Becerra and Melissa Damian; and nominate Rubio choice David Leibowitz to the Southern District. Assuming the deal holds up, nominees should hit the Senate this summer.

Meanwhile, Georgia has no current or pending judicial vacancies, although Judge Mark Treadwell on the Middle District is eligible for senior status and may take it soon.

Federal Circuit – 0 vacancies out of 12 judgeships

Biden has already named two judges to the specialized Federal Circuit, and the court has no current vacancies. However, two factors make this court one to keep an eye on. First, Judge Pauline Newman, at 96, the oldest active judge in the country, is in the middle of a disciplinary action concerning her continued fitness to remain in active status. Other judges on the court are pushing Newman to retire or take senior status, which would open a seat for Biden to fill. Second, even setting Newman aside, four other judges on the court are currently eligible for senior status, including judges Alan Lourie and Timothy Dyk, who are in their mid to late 80s. As such, the odds are in favor of an additional vacancy opening on the Federal Circuit this Congress.

Additionally, after more than two years of waiting, the White House finally named candidates to fill two vacancies on the Court of International Trade, the only Article III court that is required to have partisan balance. The candidates, a pair of a Democratic and Republican pick, should have relatively comfortable confirmations.

Conclusion

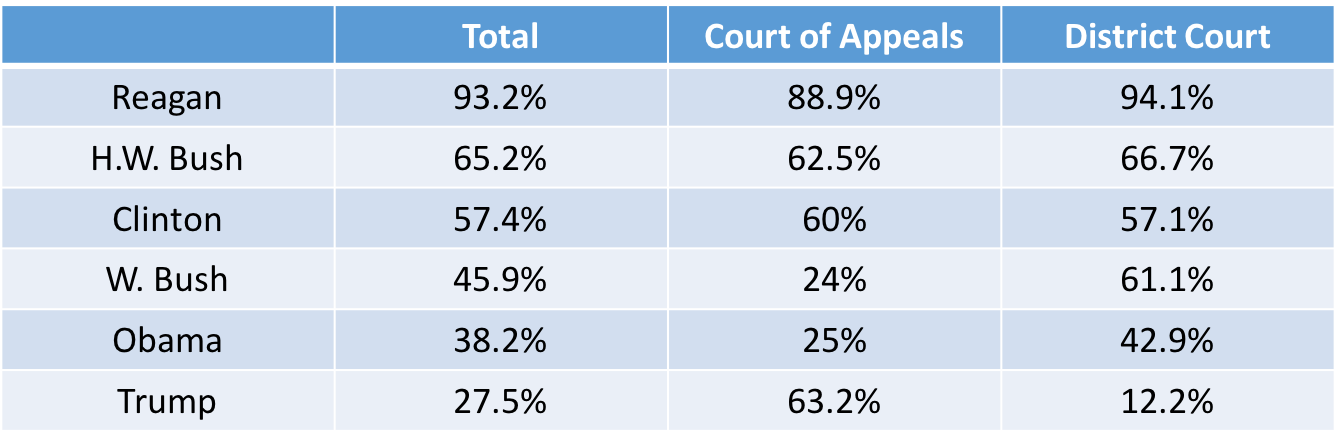

At this point, Democrats have many successes to tout in their first six months with a real majority, and have slightly exceeded their confirmation pace from the previous Congress. However, with a Presidential election looming, both the nomination and confirmation pace likely needs to accelerate further to give the Biden Administration a chance to catch up to, if not exceed, the accomplishments of the previous Trump Administration.