Judge Amy Coney Barrett has undergone a meteoric rise. On the bench for less than a year and having practiced law for only two, Barrett is now a leading contender for the U.S. Supreme Court. In the jockeying among various candidates on the shortlist, Barrett is the favorite of social conservatives, which may both hurt and assist in the nomination process.

Vital Statistics

Name: Amy Vivian Coney Barrett

Age: 46

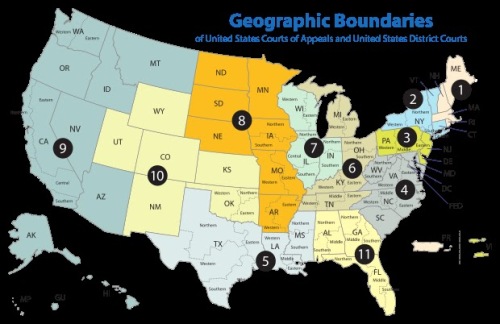

Current Position: Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit (since 2017)

Education: B.A. from Rhodes College; J.D. from Notre Dame Law School

Clerkships: Judge Laurence Silberman, U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit; Justice Antonin Scalia, U.S. Supreme Court

Prior Experience: Professor of Law at Notre Dame Law School from 2002 to 2017

Jurisprudence

Of all of Trump’s shortlist picks, Barrett has the least amount of judicial experience. She has served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit since October 2017, and has never been a judge before. In her eight months on the bench, Barrett has authored just nine opinions, only one of which drew a dissent. Her opinions are outlined below:

Criminal

- Schmidt v. Foster – This was a collateral challenge to the defendant’s murder conviction. At his trial, the defendant had sought to use a provocation defense. To ensure that the defendant had an evidentiary basis for the defense, the trial judge interviewed him in an ex parte hearing, with the defense attorney present but unable to participate. On habeas review, the majority of the Seventh Circuit overturned the conviction, finding that preventing the defendant from accessing his counsel during the ex parte hearing violated his rights under the Sixth Amendment. Barrett dissented, arguing that there was no evidence that the defendant’s rights were violated.

- Perrone v. United States – The defendant sought to withdraw a plea agreement he had made, arguing that his counsel had been deficient. The defendant argued that his counsel should have informed him that the government needed to show that his distribution of cocaine was the but-for cause of the victim’s death. Barrett rejected this argument, noting that, under the Strickland standard, the defendant would be unable to show that his deficient counsel prejudiced him.

- United States v. Barnes – The defendant, in this case, sought to challenge his sentence, arguing that the court incorrectly used his local marijuana conviction to enhance his sentence. Barrett rejected this argument, noting that the defendant failed to properly object to the enhancement, and, as such, forfeited the claim.

Civil

- Wisconsin Central Ltd. v. TiEnergy, LLC. – This case involved a suit to recover demurrage (statutory fees imposed when rail cars are unduly detained). After a Wisconsin Central car was detained at TiEnergy’s facility, Wisconsin Central filed suit to recover the demurrage incurred. Barrett wrote for the panel in finding that TiEnergy needed to reimburse the demurrage fees.

- Goplin v. WeConnect, Inc. – This case turned on whether the plaintiff-employee was bound by an arbitration agreement in resolving his Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) claim against defendant-employer. Barrett ruled that the arbitration agreement did not control, as the company mentioned in the agreement was AEI, not WeConnect. Barrett also rejected the defendant’s argument that AEI was merely the former name of WeConnect.

- Fiorentini v. Paul Revere Life Insurance Co. – The plaintiff, a business owner, received total disability coverage through insurance while undergoing cancer treatment. After being cancer-free for five years, the plaintiff returned to work, and the total disability coverage ceased. Plaintiff filed suit for breach of contract, arguing that the side effects from the cancer treatment still left him disabled under the insurance agreement. Barrett disagreed, finding that the plaintiff was able to conduct most of the essential functions of his position, and, as such, he was not totally disabled.

- Dalton v. Teva North America – The plaintiff sued the manufacturer of an intrauterine device (IUD) after it broke during its removal. Barrett affirmed the dismissal of the plaintiff’s claims, noting that Indiana law requires the use of expert evidence to prove causation, and the plaintiff had failed to present expert evidence.

- Boogard v. Nat’l Hockey League – This was a wrongful death action brought by parents of a NHL player who died of a drug overdose. Barrett affirmed the dismissal of plaintiffs’ claims, noting that the plaintiffs had failed to respond to the defendant’s 12(b)(6) motion, and had, in doing so, forfeited their claims.

- Webb v. Financial Indus. Regulatory Auth. – This case involved a breach of contract action brought against FINRA based on the failure to train arbitrators. Barrett wrote for the panel majority in dismissing the claim, finding that the amount in controversy requirement was not satisfied for diversity jurisdiction. Judge Kenneth Ripple dissented, arguing that, accepting the plaintiffs’ claims, the amount had been satisfied.

- Walton v. EOS CCA – This suit challenged a debt collector’s practices under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act. Barrett held that the collector had met their requirements under federal law.

Academic Writing

As a law professor for sixteen years before she joined the bench, Barrett was fairly prolific in detailing and explaining her view of the law. In her academic writings, Barrett occasionally took on controversial positions.

Most notably, in 2003, Barrett published an article in the University of Colorado Law Review calling into question the application of stare decisis in certain cases. The article, titled Stare Decisis and Due Process argues that, just as the due process clause limits the application of issue preclusion (or collateral estoppel), it should similarly limit the application of stare decisis. Barrett argues that a more flexible application of stare decisis is not only consistent with history, but would not impair the appropriate value of precedent. Barrett was questioned on this “flexible” view of stare decisis during her confirmation hearings, and the issue is likely to come up again if she is elevated.

Additionally, in an article titled Catholic Judges in Capital Cases, Barrett debates whether a Catholic judge would be required to recuse themselves in capital cases based on their religious objections to the death penalty. Barrett’s ultimate conclusion in the article is as follows:

“Judges cannot – nor should they try to – align our legal system with the Church’s moral teaching whenever the two diverge. They should, however, conform their own behavior to the Church’s standard.”

This conclusion led to criticism suggesting that Barrett was advocating that a judge base their decisions on church policy rather than the law. Such criticism was, in turn, dismissed by some commentators as anti-Catholic.

Why Trump Could Choose Barrett as His Nominee

In his nominee, Trump is seeking someone with Ivy League credentials and a long academic record. While Barrett is not an Ivy League alumnus, as a Supreme Court clerk, her credentials rival those of any Yale or Harvard graduate. Furthermore, Barrett has a wider and stronger academic record than any of Trump’s other finalists.

Furthermore, Barrett’s selection makes sense politically. First, Barrett is a woman, and thus, harder to caricature as a conservative extremist. Second, Barrett has strong support from social conservatives, a key constituency in the Supreme Court fight. Third, Barrett is from Indiana, putting Sen. Joe Donnelly (D-Ind.) in an impossible position. If he opposes Barrett, he risks alienating the center-right voters he needs to win re-election. If he supports Barrett, he risks alienating his own base, who he also needs. In other words, a Barrett pick would vastly increase the chances of Donnelly losing re-election, and, as such, of Republicans holding the Senate.

Why Trump Would Not Choose Barrett as His Nominee

There are three main reasons why Barrett may not be chosen as the nominee. First, Barrett does not yet have the requisite level of experience for the Supreme Court. Republicans are still wary from the nomination of Justice David Souter (an expected conservative who became a reliably liberal vote) and may seek stronger confirmation of Barrett’s jurisprudence before elevating her. Second, Barrett risks fracturing the Republican caucus. Republican Sen. Susan Collins has already indicated that she will not back any nominee who opposes Roe v. Wade or who does not commit to stare decisis. Given Barrett’s writings on the subject, her confirmation may end up being much more difficult than those of other shortlisters. Third, given the comparative paucity of female Supreme Court candidates on the right, Trump may choose to “save” Barrett for a seat vacated by a female Justice (e.g. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg).

Expected Lines of Attack

Barrett has already undergone one grueling confirmation process, receiving just three Democratic votes. If she is nominated again, expect emphasis on Barrett’s view on Roe v. Wade, given her status as the likely fifth vote on rehearing the case.

Likelihood of Nomination

Had the nomination come out this week, I’d have expected Barrett to be the nominee. However, a brutal series of attacks by social conservatives on expected frontrunner Brett Kavanaugh may have had the side-effect of weakening Barrett as well. Nevertheless, given the political benefits of nominating Barrett,a Barrett nomination should be no surprise.