Allison Eid shares a similar background to another Trump judicial nominee, David Stras: like Stras, Eid is a former academic; like Stras, she clerked for Justice Clarence Thomas; and like Stras, she serves on a state supreme court. However, unlike Stras, whose nomination is currently stymied by the opposition of a home state senator, Eid has received the requisite sign-off from her home state senators, allowing her nomination to move forward.

Background

Eid was born Allison Hartwell in Seattle, Washington in 1965. After getting a B.A. with distinction from Stanford University, Eid joined the staff of U.S. Secretary of Education William Bennett as a Special Advisor and Speechwriter. At the end of the Reagan Administration, Eid joined the University of Chicago Law School, graduating with high honors in 1991. After graduating, Eid clerked for the notoriously conservative Judge Jerry Edwin Smith on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, and went on to clerk for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, clerking at the Supreme Court in a particularly notable year for clerks (prominent co-clerks include Justice Neil Gorsuch, Paul Clement, Prof. Eugene Volokh, and federal judges Brett Kavanaugh, Gary Feinerman, J. Paul Oetken, and Brian Morris).

In 1994, at the conclusion of her clerkship with Thomas, Eid joined Arnold & Porter, working as a litigator there for four years. She left the firm in 1998, joining the University of Colorado Law School, teaching Torts, Constitutional Law, and Legislation.[1]

In 2005, Eid was tapped by Republican Attorney General John Suthers to be Colorado’s Solicitor General.[2] Shortly after, Eid was one of three finalists for a vacancy on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit (eventually filled by Gorsuch).[3] However, instead, Eid was instead nominated for a vacancy on the Colorado Supreme Court by Republican Governor Bill Owens.[4]

History of the Seat

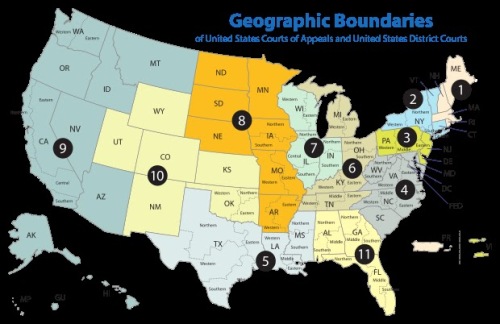

Eid was tapped for a Colorado seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. The seat was vacated by now-Justice Neil Gorsuch, who was elevated to the U.S. Supreme Court on April 9, 2017.

Like Gorsuch, Eid was also among the finalists for the Supreme Court vacancy left by Justice Antonin Scalia’s death.[5]

Political Activity

Colorado Supreme Court justices serve ten year terms, with retention elections marking the end of every term. Since her appointment in 2006, Eid has come up for retention once (in 2008) and was retained with 75% of voters in support.[6]

Other than her time in judicial elections, Eid has minimal involvement with electoral politics. She has made small contributions to former Republican senator Wayne Allard,[7] and to failed Republican congressional candidate Greg Walcher.[8]

Legal Career

While Eid has spent most of her legal career either as an academic or as a jurist, she has four years of experience in private practice working at Arnold & Porter. Among her work there, Eid was part of the legal team defending investors who recovered profits from a Ponzi scheme. Eid helped successfully defend the recovered profits against actions by bankruptcy trustees seeking “fictitious profits”.[9]

Jurisprudence

Eid has served on the Colorado Supreme Court for approximately eleven years. As the Colorado Supreme Court has discretionary review, Eid hears appeals on issues of exceptional importance, as well as constitutional challenges, death penalty cases, and certain election law issues. During her tenure, Eid has carved out a pattern as the most conservative justice on the court, frequently voting in favor of narrow interpretations of criminal and civil protections. Below are some patterns drawn from her jurisprudence.

Conservative View of Tort Remedies

A former torts professor, Eid has worked on the bench to narrow avenues for tort remedies, including limiting liability,[10] reading affirmative defenses broadly,[11] and expanding immunity.[12] In one case, for example, Eid dissented from a majority opinion that expanded the “attractive nuisance” doctrine to cover all children in Colorado.[13]

In another case, the Colorado Supreme Court eliminated the “sudden emergency doctrine”: a common law defense for defendants whose negligence was borne from responding to a “sudden emergency.”[14] In dissent, Eid noted:

“[The sudden emergency doctrine] simply repeats the standard negligence formulation that the jury is to determine whether the defendant’s conduct was reasonable under the circumstances, including circumstances that would amount to a sudden emergency…”[15]

Narrow Interpretation of Criminal Procedural Protections

Eid also takes a conservative view of criminal procedural protections, interpreting the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendments and their protections narrowly, and frequently voting against motions to suppress.

For example, in one case, Eid joined a dissent by Justice Nathan Coats arguing that revoking a defendant’s probation for refusing to answer questions posed to him did not violate his Fifth Amendment rights.[16] In another dissent, Eid argues that threatening a defendant with deportation to Iraq does not render his subsequent statements involuntary.[17]

Similarly, Eid has also generally voted against defendants who have argued for Fourth Amendment relief based on unreasonable searches and seizures.[18] For example, in one case, Eid was the lone dissenter arguing that a warrantless search of a cell-phone did not violate a defendant’s Fourth Amendment rights as the defendant had abandoned the cell-phone.[19]

Unwillingness to Consider Legislative History

Similar to Justices Scalia and Thomas, Eid refuses to consider legislative history in analyzing the meaning of statutes.[20]

For example, in one case, Eid notes:

“I join the majority opinion because I agree that under the plain language of section 10-4-110.5(1), C.R.S. (2007), Granite State’s late notice resulted in a forty-five-day extension of the old policy, but not in a full-term renewal. See maj. op. at 14. I write separately to note that I would not resort to an examination of the statute’s legislative history.”[21]

Reversals

The Colorado Supreme Court, on which Eid serves, is the final authority on the interpretation of the Colorado Constitution and statutes. As such, the only decisions of the Colorado Supreme Court that can be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court are interpretations of the U.S. Constitution or federal law.

During Eid’s eleven year tenure on the bench, only a handful of Colorado Supreme Court cases have made it up to the Supreme Court. We have outlined the key cases below.

Air Wisconsin Airlines Corp. v. Hoeper was a defamation action brought by a pilot based on statements to the TSA by airline employees questioning his mental stability. After the jury returned a verdict for the plaintiff, the Colorado Court of Appeals affirmed. The Colorado Supreme Court also affirmed the verdict in a 4-3 decision, holding that the airline employees were not immunized by Congress for their remarks.[22] Eid concurred in part and dissented in part, joined by two colleagues, arguing that the airline and its employees were immune from the defamation action under the Aviation and Transportation Security Act (ATSA), and furthermore, that the statements made were not materially false.[23] The Supreme Court granted certiorari and reversed the Colorado Supreme Court. Writing for a six justice majority, Justice Sotomayor agreed with Eid’s dissent that the challenged statements were not materially false, and that, in any case, the airline was immunized under the ATSA.[24] Justice Scalia, joined by Justices Thomas and Kagan, concurred with the opinion, agreeing with the reversal but noting that the material falsity of the challenged statements is a factual issue best left to the lower courts.[25]

Pena-Rodriguez v. Colorado involved the question of whether racial animus on the part of a juror permitted a trial judge to grant a new trial. One of the jurors in the panel that convicted Pena-Rodriguez expressed anti-Hispanic sentiments during the jury deliberations. After the trial court denied a motion for a new trial, and the Colorado Court of Appeals affirmed, the Colorado Supreme Court held on a 4-3 vote that the Colorado Rule of Evidence 606(b) barred inquiry into racist juror statements, and that such statements did not violate Pena-Rodriguez’s Sixth Amendment right to a fair trial.[26] Eid joined a dissent by Justice Monica Marquez, which argued that inquiries into racially biased statements by jurors were permitted when they compromised a defendant’s Sixth Amendment rights.[27] The U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5-3 vote agreed. Writing for the majority, Justice Kennedy found that, where there is compelling evidence that racial animus motivated a jury decision, the Sixth Amendment requires examination.[28]

Nelson v. Colorado was a challenge to a Colorado statute that required defendants whose convictions have been reversed or vacated to prove their actual innocence by clear and convicing evidence before they could get a refund of the court costs, fees, and restitution paid. The Colorado Supreme Court, in a 5-1 decision, with Eid in the majority, held that the statute was constitutional.[29] In dissent, Justice Richard Hood noted that keeping money paid by a defendant who was legally innocent was a violation of the Due Process Clause.[30] In a 7-1 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed. Writing for the majority, Justice Ginsburg found that the Colorado Statute violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of due process.[31] Only Justice Thomas, in a lone dissent, sided with the majority (and Eid).[32]

Scholarship

During her time as a law professor, Eid has written many articles discussing salient law and policy issues. We have outlined the main topics of her writings below, along with the themes on each topic.

Federalism

Eid has written extensively on constitutional structure, specifically on federalism. Specifically, Eid has analyzed New Federalism, the re-invogaration of federal structure and states rights by the Rehnquist Court. Eid defends New Federalism against critiques that it is too formalistic, arguing that the Court’s decisions striking down broad federal schemes recognize the value of federalism.[33] In another article, Eid argues that formalism in constitutional interpretation helps to “counteract the Justices’ inherent tendency to nationalism.”[34]

Similarly, Eid also argues for a limited role for the federal government in other contexts. In one article, she disputes the argument that the Property Clause of the U.S. Constitution gives the federal government broad authority to regulate environmental policy.[35] In another, she notes that the Supremacy Clause is not a “repository of congressional power” but rather a mere conflict-of-laws provision.[36]

Tort Reform

As a former torts professor, Eid has written and spoken repeatedly on tort law, usually in support of conservative tort reform.

In a 2001 symposium talk, Eid speaks approvingly of tort reform measures imposed in Colorado, including limitations on joint and several liability, and caps on punitive damages.[37] In her law review note as a student, Eid spoke in support of expanded immunity to federal civil rights actions (specifically 1983 suits) for private parties.[38] Specifically, she notes that opening public and private parties to civil rights liability could cause them to be “deterred by undue fear of frivolous litigation.”[39]

Overall Assessment

Eid is an ideal judicial candidate from a conservative perspective. She has a conservative pedigree (having clerked for Smith and Thomas) and a conservative record of jurisprudence. Furthermore, her writings on federalism and tort reform should draw support from those favoring a more right-wing judiciary.

As such, Eid will likely trigger strong opposition from Senate Democrats. They will likely argue that her judicial record shows an unwillingness to defend the rights of civil plaintiffs and criminal defendants, and will paint her as a clone of her mentor Justice Thomas. For Senate Republicans, these same qualities will be argued to be a positive. As Republicans still maintain a majority in the U.S. Senate (and as Democratic Colorado Senator Michael Bennet has returned his blue slip on Eid), there is little Democrats can do to stop her nomination.

As such, Eid is likely to bring a strong voice for limits on government power, and restrictions on tort liability to the Tenth Circuit. Democrats can take some comfort from the fact that Eid’s departure will permit Democratic Governor John Hickenlooper to make another appointment to the Colorado Supreme Court, reshaping it in a more liberal direction.

[9] See Sender v. Simon, 84 F.3d 1299 (10th Cir. 1996).

[10] See, e.g., Fleury v. IntraWest Winter Park Oper., 372 P.3d 349 (Colo. 2016) (finding that an in-bound avalanche was included among the “risks of skiing” for liability purposes).

[11] See, e.g., Hesse v. McClintic, 176 P.3d 759 (Colo. 2008) (finding sufficient evidence to submit comparative negligence instruction to jury).

[12] See, e.g., Burnett v. Colorado Dep’t of Nat. Res., 346 P.3d 1005 (Colo. 2016) (Eid, J., concurring) (finding that the plain text of the Colorado Governmental Immunity Act prevents tort relief from injury caused by tree limb).

[13] S.W. v. Towers Boat Club, 315 P.3d 1257 (Colo. 2013) (Eid, J., dissenting).

[14] Bedor v. Johnson, 292 P.3d 924 (Colo. 2013).

[15] See id. at 931 (Eid, J., dissenting).

[16] In re People v. Roberson, 377 P.3d 1039, 1049 (Colo. 2016) (Coats, J., dissenting).

[17] People v. Ramadon, 314 P.3d 836, 845 (Colo. 2013) (Eid, J., dissenting).

[18] See People v. Cox, 2017 Colo. LEXIS 88; People v. Fuerst, 302 P.3d 253 (Colo. 2013) (Hobbs, J., concurring in the judgment); People v. Arapu, 283 P.3d 680 (Colo. 2012); People v. McCarty, 229 P.3d 1041, 1046 (Colo. 2010) (Eid, J., dissenting). But see People v. Herrera, 357 P.3d 1227 (Colo. 2015) (affirming trial court suppression order).

[19] People v. Schutter, 249 P.3d 1123, 1126 (Colo. 2011) (Eid, J., dissenting).

[20] See Burnett v. Colorado Dep’t of Nat. Res., 346 P.3d 1005 (Colo. 2016) (Eid, J., concurring).

[21] Granite State Ins. Co. v. Ken Caryl Ranch Master Assoc., 183 P.3d 563, 568 (Colo. 2008) (Eid, J., concurring).

[22] Air Wisconsin Airlines Corp. v. Hoeper, 320 P.3d 830 (Colo. 2012).

[23] Id. at 842 (Eid, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

[24] Air Wisconsin Airlines Corp. v. Hoeper, 134 S.Ct. 852, 858 (2014).

[25] See id. at 867 (Scalia, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

[26] State v. Pena-Rodriguez, 350 P.3d 287, 289 (Colo. 2015).

[27] Id. at 293-94 (Marquez, J., dissenting).

[28] Pena-Rodriguez v. Colorado, 137 S.Ct. 855 (2017).

[29] State v. Nelson, 362 P.3d 1070 (Colo. 2015).

[30] Id. at 1079 (Hood, J., dissenting).

[31] Nelson v. Colorado, 137 S.Ct. 1249, 1254 (2017).

[32] Id. at 1263 (Thomas, J., dissenting).

[33] Allison H. Eid, Federalism and Formalism, 11 Wm. & Mary Bill of Rts. J. 1191 (April 2003).

[34] Allison H. Eid, Judge White and the Exercise of Judicial Power: Justice White’s Federalism: The (Sometimes) Conflicting Forces of Nationalism, Pragmatism, and Judicial Restraint, 74 U. Colo. L. Rev. 1629, 1634 (Fall 2003).

[35] Allison H. Eid, Constitutional Conflicts on Public Lands: The Property Clause and New Federalism, 75 U. Colo. L. Rev. 1241 (Fall 2004).

[36] Allison H. Eid, Pre-emption and the Federalism Five, 37 Rutgers L. J. 1, 38 (Fall 2005).

[37] Allison H. Eid, Symposium: Panel Four: Tort Law in the Federal System: An Exchange on Constitutional and Policy Considerations, 31 Seton Hall L. Rev. 740 (2001).

[38] Allison Hartwell Eid, Private Party Immunities to Section 1983 Suits, 57 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1323 (Fall 1990).