At 43 years old, Justice David Stras is the youngest appellate nominee put forward by the Trump Administration. Despite his youth, Stras, who has spent seven years on the Minnesota Supreme Court, has both the academic and judicial qualifications for the job. However, the Trump Administration’s failure, once again, to preclear Stras’ nomination with Minnesota’s senators could jeopardize a comfortable confirmation.

Background

David Ryan Stras was born in Wichita, Kansas on July 4, 1974. After getting a B.A. with highest distinction at the University of Kansas, Stras attended the University of Kansas School of Law for a joint JD/MBA program. After graduating, Stras clerked for Judge Melvin Brunetti at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, and then for conservative superstar Judge J. Michael Luttig with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. After his clerkship, Stras was hired as an associate at the Washington D.C. Office of Sidley Austin LLP.

In 2002, Stras left Sidley to take a prestigious clerkship with Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. After clerking for Thomas, Stras moved to the University of Alabama School of Law as a Hugo Black Faculty Fellow, teaching Federal Jurisdiction and Law and Economics. After his fellowship, Stras was hired as an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Minnesota Law School, where Stras taught Federal Jurisdiction and Constitutional Law.

In 2010, Stras was tapped by Republican Governor Tim Pawlenty for an opening on the Minnesota Supreme Court.[1] The appointment drew criticism both for Stras’ age (35) and inexperience, and for the timing of the appointment, coming shortly after the Supreme Court had narrowly rejected Pawlenty’s use of unallotments to reduce state spending.[2] Stras was subsequently elected to a six year term on the court and currently serves as a supreme court justice.[3]

History of the Seat

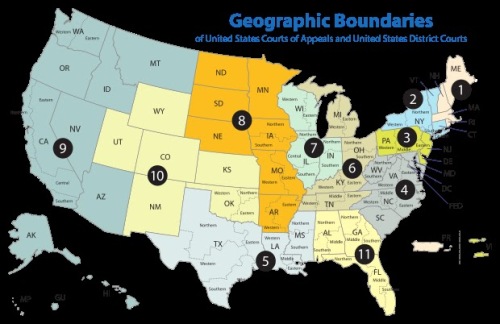

Stras was tapped for a Minnesota seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit vacated by Judge Diana Murphy. Murphy, a centrist voice on the court who was tapped for the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota by President Jimmy Carter, and elevated to the Eighth Circuit by President Bill Clinton in 1994, moved to senior status on Nov. 29, 2016.

Stras, who was on President Trump’s shortlist for the Supreme Court vacancy created by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia,[4] was contacted regarding his interest in the Minnesota seat in January 2017. He interviewed with the White House Counsel in March and was formally nominated on May 8, 2017. Stras’ nomination was met with skepticism by Minnesota Senators Amy Klobachar and Al Franken, who indicated that they were not meaningfully consulted about Stras prior to the nomination.[5]

Political Activity

Minnesota Supreme Court justices are elected to 6-year terms in nonpartisan elections. In theory, this allows candidates to run for open seats. However, since 1992, every new justice has been appointed by the Minnesota Governor and has run as an incumbent. In 2012, Stras was challenged for a full six year term by magistrate judge Tim Tingelstad and attorney Alan Nelson. Stras led the first round of balloting with 49% of the vote, and faced Tingelstad who received 29%.

In the general election, Stras emphasized his apolitical nature, and the bipartisan support he had received, while Tingelstad pushed for the elimination of court appointments.[6] Faith became a dividing line between the candidates, as Tingelstad emphasized his Christian faith, while Stras, who is Jewish, stated “I do not think that God dictates any of my decisions.”[7] In the general election, Stras defeated Tingelstad, taking 56% of the vote.[8]

Other than his run for judicial office, Stras has minimal involvement with electoral politics. His only involvement with campaigns involved attending fundraising events for Gov. Pawlenty in the years before his appointment to the Supreme Court.

Legal Career

Having spent most of his legal career either as an academic or as a jurist, Stras has comparatively little experience in the practice of law. Stras’ litigation experience consists of one year as an associate at Sidley Austin LLP., and one year serving as Of Counsel in the Minneapolis office of Faegre Baker Daniels LLP. During his time at Sidley, Stras worked on white collar criminal defense and the representations of telecommunications, railroads, and utilities on appeal. At Faegre, Stras served as an advisor on appellate and federal court matters, including the representation of a mortgage company seeking to foreclose on homes in Minnesota.[9]

Jurisprudence

Stras has served on the Minnesota Supreme Court for approximately seven years, hearing appeals from the Minnesota lower courts, and serving as the final voice on Minnesota state law. During his tenure, Stras has developed a reputation as an idiosyncratic conservative, frequently staking out liberal positions in dissent.[10] Below are some patterns drawn from his jurisprudence.

Limited View of a Judge’s Role

Throughout his tenure, Stras has frequently written concurrences and dissents criticizing his colleagues for departing from the appropriate “role of a judge.” In doing so, Stras has criticized equitable, judge-made doctrines that seek to remedy wrongdoing. Stras has been particularly critical of the “interests of justice” standard, noting in one case:

“…I continue to doubt our authority to reduce sentences or reverse convictions in the interests of justice or under some comparable, “highly subjective” power…”[11]

In another case, the Minnesota Supreme Court held that the Minnesota Department of Health must comply with the informed consent provisions of the Genetic Privacy Act before collecting blood samples from newborn children to screen for diseases.[12] In dissent, Stras noted:

“In my view, the court reaches the correct policy result. If I were a legislator, I would vote for legislation protecting blood samples under the Genetic Privacy Act. However, my role as a judge is not to implement my own policy preferences, but to interpret the law as written.”[13]

Strictness on Jurisdiction and Timeliness

Stras has also taken a very narrow view of the Minnesota Supreme Court’s jurisdiction, frequently arguing that cases should be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction, untimeliness, or mootness.[14]

For example, in one case, Stras lambasted his colleagues for deciding an appeal he deemed untimely:

“The court’s rule in the decision we announce today can be boiled down to the following proposition: we may treat the time limits for filing an appeal as optional in some cases and mandatory in others, depending on our intuition about whether judicial economy favors review.”[15]

Similarly, Stras notes in another case:

“The majority undoubtedly addresses an issue of great importance for sexual assault prosecutions in Minnesota. The majority does so, however, in a case over which we have no jurisdiction.”[16]

Willingness to Enforce Criminal Procedural Rules

Despite his conservative background, Stras’ jurisprudence is relatively friendly to those charged with crimes, interpreting the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendments and their protections strictly.

Like most judges, Stras has generally affirmed convictions against procedural arguments.[17] However, compared to his colleagues, Stras has frequently found the violation of criminal defendants’ procedural rights. In State v. Bernard, Stras dissented from a 5-2 decision holding that compelled breath tests looking for alcohol did not violate the Fourth Amendment.[18] Similarly, in State v. Brooks, Stras wrote in dissent that a driver did not voluntarily consent to a blood and urine test.[19] Specifically, Stras noted:

“It is hard to imagine how Brooks’ consent could have been voluntary when he was advised that refusal to consent to a search is a crime.”[20]

In another case, Stras held that a defendant had a Sixth Amendment right to have a jury, not a judge, determine his statutory “risk level” for sentencing purposes.[21] In yet another case, Stras joined a dissent arguing that a 21-month delay violated a defendant’s speedy trial rights under the Sixth Amendment.[22]

However, in a few cases, Stras has disagreed with colleagues who have overturned the convictions of defendants.[23] In one case, Stras found that a defendant’s waiver of counsel should be treated as knowing and voluntary even after a significant charging change by the prosecution.[24] In another case, Stras disagreed with the court majority in their ruling that the state’s attempt to interfere in the testimony of a defense expert witness required reversal of the conviction.[25]

Reluctance to Grant Postconviction Relief

While Stras has been willing to find for criminal defendants whose procedural rights were violated, he is much less friendly to defendants challenging their convictions based on trial errors or evidentiary issues. Specifically, Stras has rejected claims based on prosecutorial misconduct,[26] incorrect evidentiary rulings,[27] or sufficiency of the evidence.[28] Stras is particularly willing to dismiss collateral challenges as procedurally barred.[29]

However, Stras has shown a willingness to reverse convictions that rely on jury instructions that misstate the elements of the offense or the burden of proof.[30]

Reversals

The Minnesota Supreme Court, on which Stras serves, is the final authority on the interpretation of the Minnesota Constitution and statutes. As such, the only decisions of the Minnesota Supreme Court that can be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court are interpretations of the U.S. Constitution or federal law.

During Stras’ seven year tenure on the bench, none of his opinions have been reversed by the Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court did indirectly reverse Stras’ view in one case.

State v. Bernard was a challenge to a Minnesota law making it a crime to refuse to take a chemical test to detect alcohol in a DWI case. Bernard challenged the statute as a violation of his due process rights, as the search itself was unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment. The Minnesota Supreme Court, in a 5-2 opinion, upheld the law, arguing that chemical tests are a proper search incident-to-arrest and as such, criminalizing the refusal of the search did not implicate due process rights.[31] In a joint dissent, Stras and Justice Alan Page sharply criticized the majority’s reasoning, arguing that it was contrary to Supreme Court precedent limiting the search incident-to-arrest exception.[32]

On a consolidated appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court found that warrantless breath tests did not implicate the Fourth Amendment, essentially affirming the Minnesota Supreme Court decision, and implicitly disagreeing with Stras’ dissent.[33] Stras’ position did draw the votes of Justices Sotomayor and Ginsburg.[34]

Scholarship

During his time as a law professor, and, to a lesser extent, during his years on the Minnesota Supreme Court, Stras has written fairly extensively about the Constitution, the rule of law, and legal decisionmaking. We have outlined the main topics of his writings below, along with the themes on each topic.

Role of the Law Clerk

Both as a law professor and as a justice, Stras has written and spoken extensively on the role of law clerks in the judicial process. In a 2007 book review, Stras, a former Supreme Court clerk himself, noted the importance of law clerks who serve in the cert pool, and thus help limit the number of petitions granted by the court.[35] In another article, Stras notes the significant role that law clerks placed in the oral argument preparation for Justice Harry Blackmun.[36]

Stras has also spoken candidly on his own experience both as a law clerk and as a justice hiring law clerks. In his keynote address at the Marquette University Law School’s conference, Judicial Assistants or Junior Judges: The Hiring, Utilization, and Influence of Law Clerks, Stras explained the different roles for clerks at the Fourth Circuit, the Ninth Circuit, and the U.S. Supreme Court (where Stras clerked) as well as the Minnesota Supreme Court.[37] In the speech, Stras noted that, while he uses clerks extensively for preliminary work on cases, he does not use clerk input for oral argument.[38] At the same conference, Stras noted that he does not have a political “litmus test” for his clerks and hires clerks from all backgrounds.[39] Rather, he noted:

“I just want people with diverse backgrounds, which can include things like race, region, things like that.”[40]

Life Tenure

Stras has written and spoken repeatedly in defense of the constitutional guarantee of life tenure for federal judges.

In a 2005 law review article, Stras argued that Congress could not abrogate life tenure for federal judges without violating a number of constitutional provisions, including the tenure and salary clauses.[41] He also defended life tenure against critics in the article, noting that it insulates judges from political pressure.[42] He has further expanded on this defense using empirical evidence to counter critics of life tenure.[43]

In a 2009 panel held by the Federalist Society, Stras debated Prof. Stephen Burbank, Prof. James Lindgren, and supreme court advocate Charles Cooper in strong defense of life tenure. During his remarks, he described himself as “a fundamental Burkean conservative who believes that everything in the Constitution has very strong meaning and very strong reasons behind it.”[44] He went on to defend the uniqueness of the Judiciary, praising its “anti-majoritarian” nature.[45]

Support for Conservative Judges

Stras has gone on record multiple times praising conservative judges and judicial philosophies. In 2005, during the confirmation debate over then-Judge Samuel Alito, Stras published an editorial arguing for his confirmation. Specifically, Stras noted:

“[Justice Alito] is a mainstream conservative jurist that has shown great respect for the rule of law.”[46]

Stras also authored an article praising Justice Pierce Butler, a justice who served on the Supreme Court early in the 20th century. In the article, Stras describes Butler as “stereotypically libertarian” with a strong commitment to protecting private property rights.[47] Stras disagrees with the traditional view of Butler as a “conservative”, pointing out that Butler’s jurisprudence took a broad view of the rights of criminal defendants.[48] Stras also speaks approvingly of Butler’s opinion striking down New York’s minimum wage law as an infringement on the right to contract,[49] even while acknowledging that Butler’s broad views of private property rights did not extend to resident aliens.[50]

Overall, Stras acknowledges that Butler’s broad view of economic liberty and the right to contract are “on the wrong side of history” but nonetheless praises him as a “judicial minimalist” who decided cases in a “narrow, concise, and technical manner.”[51] Stras’ praise of Butler suggests that he would seek to emulate similar qualities on the bench.

Overall Assessment

Had the Trump Administration pre-cleared Stras’ nomination with Sens. Klobuchar and Franken, his confirmation would be all but assured. Not only does Stras have the requisite qualifications for the Eighth Circuit, his jurisprudence places him well within the mainstream of his future colleagues.

Critics of Stras’ nomination will likely draw concern from his praise of Pierce Butler and his jurisprudence on economic liberty. They could argue that, as a federal judge, Stras would seek to strike down economic and environmental regulations that he deemed violations of “liberty.” However, there is nothing in Stras’ seven-year record on the Minnesota Supreme Court that suggests a hostility to government or regulation. On the contrary, Stras’ tenure suggests that he, like Butler is a “judicial minimalist”, seeking to take the court out of policy debates and allow legislatures the freedom to legislate.

Now, Stras is still a judicial conservative, and many of his rulings will likely upset those with a more liberal view of the law. Nonetheless, he is also likely to disappoint conservatives on the bench. As a Minnesota Supreme Court justice, Stras frequently joined Justice Alan Page, one of the most liberal members of the court, in dissent against rulings by the conservative majority. It would be unsurprising if, on the Eighth Circuit, Stras frequently voted with Judge Jane Kelly (the circuit’s sole liberal voice) in holding law enforcement accountable for violations of Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendments.

In this sense, Stras is likely to emulate Justice Scalia, another conservative lion who nevertheless proved to be a criminal defendant’s best advocate on many cases. If that is the case, the federal bench will be lucky to have him.

[2] See Eric Black, Pawlenty’s Supreme Court Picks Raise Sticky and Embarrassing Issues, MinnPost, May 14, 2010, https://www.minnpost.com/eric-black-ink/2010/05/pawlentys-supreme-court-picks-raise-sticky-and-embarrassing-issues. See also Peter S. Wattson, Unallotment Conflict in Minnesota 2009-2010, Senate Counsel, State of Minnesota, June 3, 2010, https://www.senate.mn/departments/scr/treatise/Unallotment/Unallotment_Conflict_in_Minnesota.pdf.

[9] See Williams v. Geithner, Case No. 09-CV-1959 (Minn. 2009).

[11] Nose v. State of Minn., 845 N.W.2d 193 (Minn. 2014) (Stras, J., concurring).

[12] Bearder v. State of Minn. et al., 806 N.W.2d 766 (Minn. 2011).

[13] See id. at 784 (Stras, J., dissenting).

[14] See Bicking v. City of Minneapolis et al., 891 N.W.2d 304 (Minn. 2017) (Stras, J. dissenting) (arguing that the case before the court is nonjusticiable); In re Guardianship of Tschumy, 853 N.W.2d 728 (Minn. 2014) (Stras, J., dissenting) (stating that there was no case or controversy); Schober v. Comm’r of Revenue, 853 N.W.2d 102 (Minn. 2013) (Stras, J., dissenting) (arguing that the petition is untimely); Berkowitz v. Office of Appellate Cts., 826 N.W.2d 203 (Minn. 2013) (holding that the petition for relief is untimely; Carlton v. State, 816 N.W.2d 590 (Minn. 2012) (Stras, J., concurring) (expressing disagreement with the use of equitable tolling to revive untimely petitions for relief); State v. Ali, 806 N.W.2d 45 (Minn. 2011) (Stras, J., concurring) (expressing disagreement with the collateral order doctrine).

[15] Harbaugh v. Comm’r of Revenue, 830 N.W.2d 881, 885 (Minn. 2013) (internal citations omitted).

[16] State of Minn. v. Obeta, 796 N.W.2d 282 (Minn. 2011) (Stras, J., dissenting).

[17] See Sanchez v. State of Minn., 890 N.W.2d 716 (Minn. 2017); State v. McAllister, 862 N.W.2d 49 (Minn. 2015); State v. Lemert, 843 N.W.2d 227 (Minn. 2014); Ferguson v. State of Minn., 826 N.W.2d 808 (Minn. 2013); State v. Ortega, 813 N.W.2d 86 (Minn. 2012); State v. Brist, 812 N.W.2d 51 (Minn. 2012). See also State v. Beecroft, 813 N.W.2d 814 (Minn. 2012) (Stras, J., dissenting); State v. Rhoads, 813 N.W.2d 880 (Minn. 2012) (Stras, J. dissenting).

[18] State v. Bernard, 859 N.W.2d 762, 774 (Minn. 2015) (Page J. and Stras J., dissenting jointly).

[19] State v. Brooks, 838 N.W.2d 563, 573 (Minn. 2013) (Stras, J., dissenting). See also State v. Fawcett, 884 N.W.2d 380 (Minn. 2016) (Stras, J., dissenting) (stating that a search for alcohol and controlled substances in a blood test violates the Fourth Amendment when the warrant only mentions alcohol).

[20] Id. at 573-74 (internal citations omitted).

[21] State v. Ge Her, 862 N.W.2d 692 (Minn. 2015).

[22] State v. Osorio, 891 N.W.2d 620, 633-38 (Minn. 2017) (Hudson, J., dissenting).

[23] See, e.g., United States v. Sydnor, No. CR 16-21-ART-HAI-(2), 2017 WL 772341, at *6 (E.D. Ky. Feb. 28, 2017) (suppressing non-Mirandized statement as elicited in violation of the Fifth Amendment).

[24] State v. Rhoads, 813 N.W.2d 880 (Minn. 2012) (Stras, J. dissenting).

[25] See State v. Beecroft, 813 N.W.2d 814 (Minn. 2012) (Stras, J., dissenting).

[26] See Hooper v. State, 838 N.W.2d 775 (Minn. 2013); State v. Hill, 801 N.W.2d 646 (Minn. 2011).

[27] See State v. Horst, 880 N.W.2d 24 (Minn 2016); Bobo v. State, 820 N.W.2d 511 (Minn. 2012) (Stras, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part); State v. Tanksley, 809 N.W.2d 706 (Minn. 2012). See also State v. Pass, 832 N.W.2d 836 (Minn. 2013) (reversing trial court exclusion of evidence as substantially prejudicial to defendant). But see Caldwell v. State, 853 N.W.2d 766 (Minn. 2014) (granting evidentiary hearing to defendant).

[28] See State v. Bahtuoh, 840 N.W.2d 804 (Minn. 2013); State v. Hayes, 826 N.W.2d 799 (Minn. 2013); State v. Hohenwald, 815 N.W.2d 823 (Minn. 2012). But see State v. Nelson, 842 N.W.2d 443 (Minn. 2014) (reversing conviction for insufficiency of the evidence).

[29] See Gail v. State, 888 N.W.2d 474 (Minn. 2016); Davis v. State, 880 N.W.2d 373 (Minn. 2016); Taylor v. State, 874 N.W.2d 429 (Minn. 2016); Wayne v. State, 870 N.W.2d 389 (Minn. 2015); Williams v. State, 869 N.W.2d 316 (Minn. 2015); Lussier v. State, 853 N.W.2d 149 (Minn. 2014); Wallace v. State, 820 N.W.2d 843 (Minn. 2012); Buckingham v. State, 799 N.W.2d 229 (Minn. 2011).

[30] See, e.g.,State v. Struzyk, 869 N.W.2d 280 (Minn. 2015) (Stras, J., concurring); State v. Kelly, 855 N.W.2d 269 (Minn. 2014) (Stras, J., concurring); State v. Koppi, 798 N.W.2d 358 (Minn. 2011).

[31] State v. Bernard, 859 N.W.2d 762, 764 (Minn. 2015).

[32] See id. at 774 (Page, J., and Stras, J., jointly dissenting).

[33] See Birchfield v. North Dakota, 136 S. Ct. 2160 (2016).

[34] See id. at 2187 (Sotomayor, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

[35] David R. Stras, The Supreme Court’s Gatekeepers: The Role of Law Clerks in the Certiorari Process, 85 Texas L. Rev. 947 (2007).

[36] Timothy R. Johnson, David R. Stras, and Ryan C. Black, Advice from the Bench (Memo): Clerk Influence on Supreme Court Oral Arguments, 98 Marq. L. Rev. 21 (Fall 2014).

[37] David R. Stras, Keynote Address: Secret Agents: Using Law Clerks Effectively, 98 Marq. L. Rev. 151 (Fall 2014).

[39] Chad Oldfather, Panel Discussion: Judges’ Perspective on Law Clerk Hiring, Utilization, and Influence, 98 Marq. L. Rev. 441 (Fall 2014).

[41] David R. Stras and Ryan W. Scott, Retaining Life Tenure: The Case for a “Golden Parachute”, 83 Wash. U. L. Q. 1397 (2005).

[43] See David R. Stras, The Incentives Approach to Judicial Retirement, 90 Minn. L. Rev. 1417 (May 2006); David R. Stras and Ryan W. Scott, An Empirical Analysis of Life Tenure: A Response to Professors Calabresi and Lindgren, 30 Harv. J. L. & Pub Pol’y 791 (Summer 2007).

[44] Federalist Society Transcript: Showcase Panel II: Judicial Tenure: Life Tenure or Fixed Non-Renewable Terms?, 12 Barry L. Rev. 173 (Spring 2009).

[47] David R. Stras, Pierce Butler: A Supreme Tactician, 62 Vand. L. Rev. 695, 717-720 (March 2009).

[48] See id. at 721 (citing Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438, 486-88 (1928) (Butler, J., dissenting)).

[49] See id. at 727 (citing Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo, 298 U.S. 587 (1936)).