“Unconfirmed” seeks to revisit nominees who were never confirmed to lifetime appointments, to explore the factors why, and to understand the people involved.

If you’ve been nominated to the federal bench, the best case scenario you hope for is that your nomination draws little attention or controversy and that you slide through the process fairly anonymously. While many judges achieve this, occasionally, a nominee is drawn into a bigger conflict and becomes a pawn in a fight between Congress and the Administration. This Black History month, we recount one such contentious nominee: Judge Frederica Massiah-Jackson.

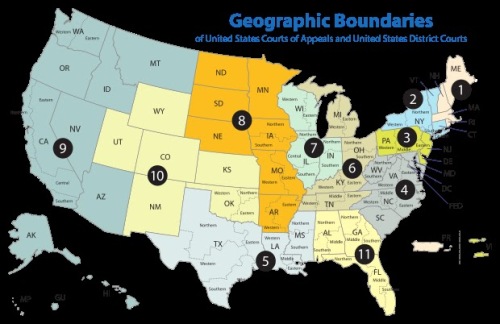

Long before her nomination sparked numerous floor fights, Massiah-Jackson was making waves as a student, graduating from Philadelphia Girls High School at just sixteen and finishing law school at the University of Pennsylvania at age 23.[1] After a clerkship at the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, and seven years in private practice, Massiah-Jackson was elected to be a judge on the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas at just 33 years old. Starting in 1992, Massiah-Jackson also began lecturing at the Wharton School, teaching Legal Studies and Business Law. As such, when President Clinton tapped her to be the first female African-American judge on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, it seemed the capstone to an already impressive career.

There were no signs of trouble early in Massiah-Jackson’s nomination. While she had established a reputation as a “liberal, outspoken judge,”[2] she also boasted the support of Pennsylvania’s U.S. Senators Arlen Specter and Rick Santorum, both Republicans.[3] Even as Massiah-Jackson’s nomination was left off a September 1997 hearing that two other Pennsylvania nominees appeared at,[4] Judiciary Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (R-UT) assured Specter that Massiah-Jackson’s questionnaire had arrived late to the Committee, and that she would be scheduled for the next hearing.[5]

Unfortunately, the confirmation quickly began to get rocky. At her hearing in October 1997, Massiah-Jackson faced a series of skeptical Republican senators, with Sen. Jon Kyl (R-AZ) criticizing her use of profanity from the bench in an early case, while Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-AL) called out her rulings in favor of criminal defendants, suggesting that Massiah-Jackson lacked “sufficient respect for prosecutors’ burdens and problems.”[6] Massiah-Jackson pushed back against that assertion, arguing that “a close reading” of her record would show no pattern of leniency to defendants.[7]

Despite the tenor of the questioning, Specter and Santorum maintained their strong support for Massiah-Jackson and she was approved by the Senate Judiciary Committee in November 1997 on a 12-6 vote.[8] As the senate prepared to recess, Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott (R-MS) teed up a floor vote in early January 1998.[9]

However, a quick confirmation for Massiah-Jackson was derailed by two incidents. First, Northampton County District Attorney John Morganelli, a conservative Democrat, announced in early January that he would conduct an “all-out-effort” to block Massiah-Jackson, calling her “anti-police and anti-prosecutor.”[10] Morganelli was soon joined by the opposition of Philadelphia District Attorney Lynne Abraham and the Pennsylvania District Attorney’s Association.[11] Additionally, Pennsylvania Attorney General D. Michael Fisher (a future federal judge himself) also weighed in against Massiah-Jackson.[12] With Pennsylvania prosecutors crusading against Massiah-Jackson’s nomination, Senate Republicans delayed the confirmation vote.

Second, the slow pace of judicial confirmations and the rapid rise in judicial vacancies prompted a rare rebuke of the Senate from both Chief Justice William Rehnquist and President Clinton in his State of the Union address.[13] Called out from both branches, Senate Republicans were eager to show that Clinton was putting forward unqualified nominees by defeating one in a floor vote.[14] With Morganelli’s and Abraham’s prominent opposition, Republicans focused on Massiah-Jackson as the ideal test case.

Critics of the Massiah-Jackson nomination made two primary charges against her: first, they pointed to her rulings against the prosecution in 4-5 cases to allege that she had an anti-prosecution and anti-police bias; second, they cited her use of profanity in two cases, and her admonishment from a disciplinary tribunal, to suggest the lack of a proper judicial temperament.[15] In response, Massiah-Jackson’s supporters accused her critics of “cherry-picking” her record and suggested that the criticism was racially motivated.[16]

Hoping to avoid further acrimony, Specter and Santorum convened a meeting between Massiah-Jackson and critical prosecutors, hoping to have their concerns addressed directly.[17] Unfortunately, the meeting did not yield a breakthrough, and the senators reluctantly agreed to delay the senate vote further to allow critics to put together “the best evidence against [Massiah-Jackson].”[18]

Unfortunately, by this point, Senate Republicans were coalescing against the nomination. Confident of defeating Massiah-Jackson, Lott pushed for a quick vote.[19] However, hoping to salvage the nomination, Specter pushed for a second hearing to allow Massiah-Jackson to publicly refute the charges against her.[20] In an emotional exchange, Specter clashed on the senate floor with Sen. John Ashcroft (R-MO), with Ashcroft declaring that any senator supporting Massiah-Jackson was “betraying our oath of office,” prompting Specter to call it a “personal insult.”[21] Ultimately, Specter and Santorum won the day: Massiah-Jackson was pulled back into Committee for a second hearing.[22]

At her second hearing, Massiah-Jackson answered critics over three and a half hours, professing her support for law enforcement and prosecutors.[23] However, alongside previous criticism, a new line of questioning emerged, with Massiah-Jackson accused of “outing” two undercover police officers at a court hearing.[24] Despite Massiah-Jackson’s supporters arguing that there was no record of the alleged incident, and that, even in the critics’ telling, it was impossible to “out” an officer who had just testified, the allegations were sufficient to draw Hatch, who had previously supported Massiah-Jackson, into opposition.[25]

With the second hearing concluded, the senate prepared for a final vote. However, Specter once-again demanded a delay to allow Massiah-Jackson a chance to respond to the recent allegations.[26] However, the vote was rapidly becoming a foregone conclusion, with even Santorum announcing that he would not support the nomination.[27] Four days later, Massiah-Jackson withdrew her nomination, stating that she could not remain silent as a nominee and allow “selected, one-sided and unsubstantiated charges to go unanswered.”[28] With her withdrawal, she managed to avoid defeat in an up-or-down vote.

Regardless of whether one accepts the criticisms against Massiah-Jackson, it is difficult to argue that the confirmation process served her well. Rather, the drip-by-drip release of allegations against Massiah-Jackson, allegations that she, bound by the ethical requirements of a judicial nominee, could not publicly refute, essentially ensured that unsubstantiated claims went unanswered. As Specter noted in a fiery floor speech, when Massiah-Jackson was given no notice as to the allegations against her, it was “impossible for her to respond in a way which would convince fairminded people as to what the facts were.”[29] Furthermore, while Specter, Santorum and many Philadelphia attorneys went to bat for Massiah-Jackson, she received little public support from the Clinton Administration, who quickly replaced her as a nominee with Judge Robert Freedberg, a white male.[30]

Ultimately, the Massiah-Jackson saga left lingering divisions in Philadelphia, with many african american voters upset at Abraham for her role in the battle.[31] For her part, Massiah-Jackson was able to stay on the state bench, where she continues to serve to this day. In an ironic turn of fate, in 2017, Massiah-Jackson led the team of judges that selected Kelley B. Hodge an interim D.A. in Philadelphia upon the resignation of Seth Williams. Among the candidates rejected for the position: Massiah-Jackson’s old foe Lynne Abraham.

[2] Joseph Slobodzian, Former Pa. Justice, City Judge Named to Federal Court/Bruce W. Kauffman and Judge Frederica Massiah-Jackson Were Among 13 Picked by Clinton, Philadelphia Inquirer, Aug. 2, 1997.

[4] See Nominations of Marjorie O. Rendell (U.S. Circuit Judge); Bruce W. Kauffman, Richard A. Lazzara, and A. Richard Caputo (U.S. District Judges), 105th Cong. 13 (1997) (statement of Sen. Arlen Specter).

[6] Steve Goldstein, Phila. Judge Grilled By Senate Panel: A Chilly Aura Pervaded the Hearing for the Federal Court Nominee, Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 30, 1997.

[8] See Chris Mondics, Senate to Vote on Phila. Judge’s Nomination, Philadelphia Inquirer, Nov. 14, 1997.

[10] Robert Moran, D.A. Out to Block Phila. Judge’s Nomination to U.S. Bench, Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 7, 1998.

[11] See Linda Lloyd, Pa. District Attorneys’ Group Votes to Oppose Phila. Judicial Nominee, Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 9, 1998.

[12] See City & Region, Pa.’s Attorney General Opposes Massiah-Jackson, Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 30, 1998.

[14] See Chris Mondics, U.S. Bench Vacancy Splits GOP in Senate, Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb. 11, 1998.

[15] See Michael Matza, The Cases Behind the Massiah-Jackson Controversy/ Prosecutors Say the Judge is Harsh on Them and Lenient in Sentencing. Defense Lawyers Praise Her Decisions, Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 21, 1998.

[16] Suzette Parmley, Blacks Denounce D.A./ A Group of Leaders Wants Lynne Abraham Recalled for the way She Opposed the Nomination of Judge Frederica Massiah-Jackson to the Federal Bench, Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 13, 1998.

[17] See Michael Matza, Massiah-Jackson Vote is Postponed in Senate/ Sens. Specter & Santorum Give Her Critics A Week to Make Their Case, Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 24, 1998.

[19] Chris Mondics, Senator Doubts Judge’s Chances/Sen. Rick Santorum Said the Votes Are Not There for Frederica Massiah-Jackson’s Nomination, Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb. 5, 1998.

[20] Chris Mondics, Specter Asks More Hearings for Judge Massiah-Jackson/ Her Nomination to the Federal Bench is in Trouble. The Senator Thinks Another Session Could Change That, Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb. 6, 1998.

[21] Chris Mondics, US Bench Vacancy Splits GOP in Senate/ Republicans Spoke Out Emotionally For and Against Clinton’s Nomination of Frederica Massiah-Jackson, Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb. 11, 1998.

[23] Chris Mondics, Judge Answers Her Critics/ Massiah-Jackson Tells Senators She Backs Police, Prosecutors, Philadelphia Inquirer, Mar. 12, 1998.

[24] Michael Matza, Courtroom ‘Outing’ Ignites Latest Fire Around Judge/ Frederica Massiah-Jackson Allegedly Pointed Out Two Undercover Narcotics Officers, But this ‘Smoking Gun’ May be Just Smoke, Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb. 15, 1998.

[26] Chris Mondics, Massiah-Jackson Voting is Delayed/ Sen. Specter Wanted Her to Have Time to Respond in Writing to the Latest Allegations, Philadelphia Inquirer, Mar. 13, 1998.

[28] AP, Controversial Judge Withdraws as Nominee to Federal Bench, N.Y. Times, Mar. 17, 1998.

[29] See 105th Cong. Rec. S3618 (daily ed. Mar. 16, 1998) (statement of Sen. Specter).

[30] The seat was ultimately filled by another african american female: Judge Petrese Tucker.

[31] See Tom Infield, Abraham Faces a Genuine Challenge; Though the D.A. is Favored to Win Re-election, Some Black Philadelphians View Her as a Symbol of a Biased System, Philadelphia Inquirer, May 13, 2001.