A century ago, Congress, responding to a changing legal landscape, fundamentally altered the operation of the federal judiciary by implementing “senior status,” allowing judges to continue working on a reduced caseload instead of retiring. Since then, judges have used senior status extensively. However, over the last thirty years or so, moves to senior status have become increasingly strategic, with judges timing their moves to allow like-minded successors to be confirmed. This has culminated, in the last four years, with the widespread use of a formerly rare maneuver, taking senior status upon confirmation of your successor. With a new Administration approaching, it is worth looking at the history of senior status, strategic retirements, and the likelihood that “senior status upon confirmation” will likely be the new normal.

What is Senior Status

Before 1919, federal judges were permitted to retire at age seventy, as long as they had at least ten years of service, after which they would maintain a pension for the rest of their life. However, under the new system created by Congress, judges could, instead of retiring, move to senior status, which allowed them to continue to work and hear cases, but nonetheless open up a vacancy for the President to fill.

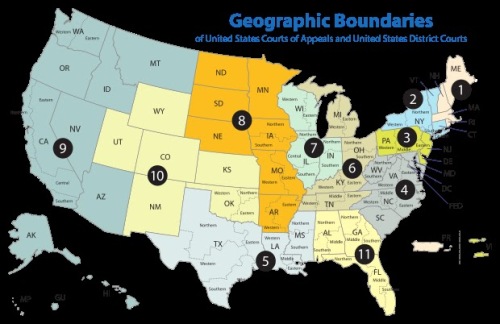

On October 6, 1919, Judge John Wesley Warrington on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit became the first judge in U.S. history to take senior status, a position he maintained until his death on May 26, 1921. In the century after Judge Warrington’s move, senior status has become the norm for federal judges, and it’s easy to see why. A judge’s move to senior status essentially adds a judge to a court, as a new judge can now be appointed while the old still hears cases. Senior judges have proven to be a boon for the federal judiciary, continuing to hear and move cases along even as caseloads expand and proposals for new judgeships stagnate. Senior status also carries benefits for the judge themselves. Unlike judges who retire from the bench, senior judges continue to be eligible for cost-of-living increases. Additionally, they retain significantly more flexibility over their dockets, allowing them to travel and to focus on cases that are more interesting to them.

Eligibility for Senior Status

At the time that the senior status system was created, a judge became eligible for senior status after ten years of service, if he or she was over the age of seventy. In 1954, this requirement was revised to the “Rule of 80.” Under this rule, any judge over the age of sixty five becomes eligible for senior status once their age + their tenure equals or exceeds 80. In other words, a judge appointed at 50 (or younger) becomes eligible for senior status at age 65. Similarly, a judge appointed at 55 becomes eligible at age 67.5 (when 67.5 + 12.5 years of service = 80). However, there is a requirement of ten years of service on the federal bench for a judge to become eligible for senior status. As such, a judge appointed at age 64 wouldn’t become eligible at age 72 but rather at 74, once the ten year minimum is satisfied. Like every rule, there are exceptions, and judges can take senior status early if justified by health concerns or because of a certified disability.

Strategic Retirements and Senior Status Upon Confirmation

Given the caseload benefits of adding an extra judge, many jurisdictions have an informal policy that judges will take senior status immediately upon eligibility. (In 2013, Judge Richard Kopf of the District of Nebraska confirmed that his district had such a policy.) However, many other judges, particularly appellate judges, do tend to be more “strategic” with their moves to senior status, timing their moves to allow like-minded successors.

Of course, such strategic considerations are not a recent development. Justice Thurgood Marshall famously resisted retirement through the 1980s, waiting for a Democratic Administration that came too late to replace him. However, strategic retirements have grown increasingly more common in the last decade with the use of a formerly-rare tool, senior status upon confirmation.

Taking senior status upon confirmation is a relatively straightforward concept. Instead of announcing a date on which he or she would vacate their seat, a judge declares their intention to take senior status contingent upon the confirmation of a successor. This prevents a vacancy from opening until a replacement was approved. Now, where a judge wishes to retire, this mechanism makes sense, as it reduces the disruption from a court losing a judge without gaining a replacement. However, a judge on senior status can easily maintain their full caseload and avoid disruption, and, as such, this mechanism has a different purpose: ensuring that the current President is able to appoint their successor. If a judge announces that they will take senior status upon confirmation and their President of choice is unable to appoint a replacement before the end of their term, the judge can (at least in theory) withdraw their intention and hold the seat without leaving a vacancy for the new President.

Perhaps because such a move could be seen as blatantly partisan, taking senior status upon confirmation has been fairly rare for much of the 20th century. In 1968, Chief Justice Earl Warren announced his retirement from the Supreme Court contingent upon the appointment of a successor. However, President Lyndon Johnson’s nomination of Justice Abe Fortas failed and the Republican Richard Nixon was elected instead. According to historian Ed Cray, Warren considered withdrawing his retirement after Nixon’s election, but decided against it, feeling that the move would be seen as “a crass admission that he was resigning for political reasons.”

Similarly, on the lower court level, taking senior status upon confirmation was practically unheard of until the second Bush Administration. In 2003, Judge John Louis Coffey of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, an appointee of President Reagan, was the first judge, reflected on the U.S. Courts website, to announce a move to senior status upon confirmation of his successor. In September 2003, Judge Emory Widener of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, who previously announced that he would take senior status on September 30, modified his status to reflect a move to senior status upon confirmation of his successor (DOD attorney William J. Haynes, nominated on September 29, 2003). The next month, Judge James Graham on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio, who had previously announced that he would take senior status on May 1, 2004, changed his status to taking senior status upon confirmation of his successor.

For their part, this strategy had mixed results. Both Graham and Coffey took senior status in 2004, upon the confirmations of Judges Michael Watson and Diane Sykes respectively. However, Haynes was blocked from confirmation for four years by the opposition of Senate Democrats and Sen. Lindsay Graham. Widener, facing ill health, finally took senior status unconditionally on July 17, 2007, and passed away two months later. His seat was ultimately filled by President Obama with Judge Barbara Keenan.

Taking senior status upon confirmation did not resurface until June 2007, when Judge Daniel Manion, another conservative Reagan appointee on the Seventh Circuit, announced that he would move to senior status upon confirmation of his successor. The next month, Judge Rudolph Randa on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin announced his intention to take senior status upon confirmation. By the end of the Bush Administration, two other judges had announced a move to senior status contingent upon confirmation: Judge John Shabaz on the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin; and Judge Garr King of the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon. For their parts, Manion was replaced by Bush appointee Daniel Tinder, but the Senate did not confirm Bush’s nominees to replace Randa, Shabaz, or King. Upon the election of President Barack Obama in 2008, Randa did what Warren had not forty years earlier, and withdrew his decision to take senior status, essentially acknowledging that he did not want a Democrat to replace him. In contrast, both Shabaz and King moved to senior status unconditionally in 2009, and President Obama replaced both judges.

Taking senior status upon confirmation was sporadically (if rarely) used under President Obama, with five judges taking that route: Judge Barbara Crabb on the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin; Judge Lawrence Piersol on the U.S. District Court for the District of South Dakota; Judge Frederick Motz on the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland; Judge Claudia Wilken on the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California; Judge Gary Fenner on the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Missouri. All had their successors appointed by President Obama. Notably, not a single appellate judge who took senior status under President Obama chose to do so contingent upon the confirmation of their successor. As such, a number of Democratic appointees who took senior status late in the Obama Administration left their seats open for President Trump to fill.

In contrast, the “senior status upon confirmation” phenomenon exploded under President Trump. In his first year alone, President Trump saw five judges announce moves to senior status contingent upon confirmation: Judge Edith Brown Clement on the Fifth Circuit; Judges David McKeague and Alice Batchelder on the Sixth Circuit; Judge Paul Kelly on the Tenth Circuit; and Judge Frank Hull on the Eleventh Circuit. In 2018, five more joined the list: Judge Allyson Kay Duncan on the Fourth Circuit; Judge Edward Prado on the Fifth Circuit; Judges John Rogers and Deborah Cook on the Sixth Circuit; and Judge Roger Wollman on the Eighth Circuit. In 2019, you had four: Judge Carlos Bea on the Ninth Circuit; and Judges Gerald Tjoflat, Stanley Markus, and Ed Carnes on the Eleventh Circuit. In other words, there were more judges taking senior status upon confirmation under President Trump than had been in the entire history of America before then.

What explains the flood of such announcements under President Trump? For one, the White House has been proactive about contacting and pushing judges to take senior status in an effort to open vacancies. Judge Michael Kanne on the Seventh Circuit described a call from the White House, where they promised to appoint one of his former clerks, Solicitor General Tom Fisher, if Kanne moved to senior status. Kanne agreed and announced his intention. However, the White House did not nominate Fisher, due to opposition from Vice President Pence, and Kanne withdrew his intent. The 82 year old judge still serves on the Seventh Circuit. It is possible that taking senior status upon confirmation allowed the judges to maintain some degree of control over their successors.

Senior Status Strategies Under President Biden

After 54 appointments to the U.S. Court of Appeals, one could think that President Trump has emptied the bench of older Republican appointees, but that’s not true. There remain twenty-six Republican appointed appellate judges who are eligible for senior status (an additional seven will become eligible over the next four years). Nonetheless, a disproportionate share of judges likely to take senior status are expected to be Democratic appointees, making the next four years likely the first in over three decades to have more Democratic appointees leave the bench than Republican ones. There are currently thirty-six Democratic appellate appointees eligible for senior status, and an additional thirteen that will become eligible over the next four years. As such, if the Democratic appointees take senior status in the traditional manner and Republicans avoid confirming replacements, this would have the effect of making the bench significantly more conservative.

As a result, one could expect Democratic appointees to follow the precedent of the Trump years and take senior status only upon confirmation of their successors. For those who are strategically inclined, this would disincentivize holding the vacancies open indefinitely and ensure that, while nominees remain pending, their circuits wouldn’t miss the judges’ voices on en banc issues. Given that many judges are already mulling “strategic” moves to senior status, it wouldn’t be surprising to see many left-of-center jurists making their moves to senior status conditional over the next four years.

How is there a vacancy to be filled by appointment and confirmation until senior status is actually taken?

LikeLike

Once a judge announces his or her intention to take senior status, the White House and Senate can treat that seat as open for purposes of nominating and confirming a successor. Others have raised the question you have, but most actors have concluded that the vacancy is fillable once it’s announced. That’s also consistent with past practice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hum. Your logic doesn’t hold water. When a judge retires/takes senior status “upon confirmation” it is no more likely they are motivated by having a like minded judge replace them than say a democrat appointed judge who retired/took senior status in 2009-2014.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How can the president appoint, and the senate confirm, a nominee to a future rather than present vacancy?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Taking senior status upon confirmation of one’s successor may not indicate that the Judge is especially political, but simply realizes that the confirmation process has become much more politicized in recent years. Judge Frank Hull was a Clinton appointee taking senior status up on confirmation during the Trump Administration. Similarly, Allyson Duncan was a compromiser selection unanimously confirmed for the 4th Circuit, who also went that route during Trump’s tenure. They may have just decided that if the nomination/confirmation process takes 6-12 months, with no guarantee of the outcome, they might as well stick around for the en banc cases.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Here Come the Retirements? | The Vetting Room

Here’s a good old article from 2005. Let’s see if any of the names mentioned become federal judges…

https://web.archive.org/web/20081013062520/http://www.observer.com/node/51498

LikeLike

Other than Kermit Roosevelt (who should have been nominated in 2014 instead of Cheryl Krause) and Richard Primus, I’m not a fan of appointing many of them to the bench. Noah Feldman is an absolute no, given that he is not much of a progressive and supported Justice Barrett’s nomination to the Supreme Court.

Also many of them are now in their 50s.

But this article suggests exactly the legal culture that we have been dealing with that has resulted in the federal bench being dominated by AUSAs and corporate law partners.

LikeLike

That’s true. I am happy President Biden has broadened the pool that is normally used to find judicial nominees. That in addition to not using the ABA vetting process which is an absolute disaster for progressive nominees, particularly those of color.

LikeLike

https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/public-defender-bench-aspirations-emboldened-by-biden-nominees?context=search&index=0

LikeLike