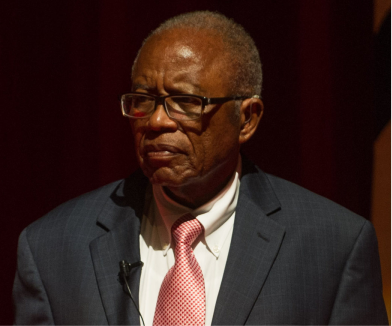

Judicial confirmation is a business. Over the last thirty years, a cottage industry of interest groups, nonprofits, and lobbying agencies have formed to support and oppose judicial candidates. Behind the rhetoric on both sides, it is sometimes easy to forget that nominees are people: people who are frequently forgotten once their nominations are blocked or defeated. “Unconfirmed” seeks to revisit nominees who were never confirmed to lifetime appointments, to explore the factors why, and to understand the people involved. On this Martin Luther King Day, where better to start this series than with one of King’s fellow civil rights leaders, whose rejection for the federal bench was laced with allegations of racism and prejudice: Fred Gray.

When Jimmy Carter was elected Governor of Georgia in 1970, Fred Gray was already one of the most famous civil rights attorneys in the nation. A native Alabamian, Gray was born in Montgomery in 1930, and grew up in a segregated city. While attending an all-black school, Gray worked as a “boy preacher”, ministering to interracial crowds throughout his youth.[1] After graduating from the Alabama State College for Negroes in 1951, Gray found himself barred from admission at an Alabama law school due to his race. Nevertheless, Gray attended Case Western Reserve School of Law in Ohio, getting a J.D. in 1954, and returning to Montgomery shortly thereafter to fight segregation.

Back in Montgomery, Gray represented Rosa Parks and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in litigation stemming from the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, as well as serving as lead counsel in Browder v. Gayle, which desegregated city buses nationwide.[2] Gray also represented King in his tax evasion case, securing an acquittal from an all-white jury.[3] Gray also successfully argued that Alabama State students who were expelled for participating in student sit-ins had their due-process rights violated, and successfully filed to protect marchers seeking to march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965.[4]

Furthermore, Gray also argued on behalf of African Americans at the Supreme Court in Gomillion v. Lightfoot.[5] Among his other accomplishments, Gray was the leading attorney in successfully desegregating the University of Alabama and Auburn University, despite the opposition of politicians including Gov. George Wallace.[6] In one of his most notable cases, Gray represented the African American victims of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.[7] Finally, in 1970, Gray was the first African American elected to the Alabama legislature, alongside Thomas Reed.[8]

When Carter was elected president in 1976, he and Attorney General Griffin Bell met with Coretta Scott King and assured her of their commitment to place qualified African American judges on the federal bench.[9] In 1979, Gray was one of five candidates considered by Carter and Bell for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.[10] Despite his commitment to King, and Gray’s strong backing from Alabama African American groups, Bell declined to recommend Gray for the seat, ranking him fifth out of the five candidates being considered.[11] The nomination and the seat instead went to the candidate ranked fourth, a white lawyer named Robert Vance.[12]

Instead, in 1979, Gray was recommended by Alabama Senators Howell Heflin and Donald Stewart (both Democrats) for a seat on the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama.[13] However, despite the recommendation, the Carter Administration sat on Gray’s nomination for several months, allegedly due to Bell’s opposition.[14] It took the personal intervention of Alabama African American power broker Joe Reed to break the impasse and allow Gray to be nominated officially in January 1980.[15]

Unfortunately for Gray, more obstacles stood ahead. Citing Gray’s alleged misconduct on a bond issue as Tuskegee City Attorney, the American Bar Association (ABA) rated Gray “unqualified” for a federal judgeship.[16] Additionally, Sen. Edward Kennedy, Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, was challenging Carter in the Democratic Presidential Primary and believed that Gray’s nomination was intended to “buy” black votes in the Alabama Democratic primary.[17] This gave him little incentive to disregard the ABA rating and move ahead on Gray’s nomination.

In response to the ABA rating, the National Bar Association, which is predominantly African American, stepped in to rate Gray and fellow black nominee U.W. Clemon, rating them “very well qualified.”[18] In May 1980, Gray finally came before the Senate Judiciary Committee, sitting through a marathon 12-hour hearing.[19] At the hearing, Gray’s supporters, including Clarence Mitchell from the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, argued that the ABA’s opposition to the nomination was tinged by racism.[20] In response, the ABA, represented by San Francisco attorney Robert D. Raven, fought back, noting:

“Do you think we want to find black judges unqualified? Do you think we’re fools?”[21]

Ultimately, the hearing did not result in further action on Gray’s nomination. In August 1980, Heflin withdrew his support for Gray.[22] Facing certain defeat, Gray withdrew his nomination.[23] In Gray’s place, Carter nominated an African American attorney in private practice in Montgomery, Myron Thompson.[24] Despite Thompson being only thirty-three years old, he received a “qualified” rating from the ABA and was confirmed on September 26, 1980.[25]

Looking back on Gray’s short-lived judicial nomination, it is difficult to take race out of the equation. Even if one accepts that the ABA’s rating was not based on Gray’s race (and there were many, even in 1980, who did not), it is hard to accept the conclusion that Gray, given his distinguished career, was unqualified for the federal bench where a thirty three year old attorney was not. Nevertheless, while Gray was not able to take the bench, he broke barriers nonetheless. In 2001, Gray became the first black president of the Alabama Bar and continues to be a civil rights leader today.[26] Ultimately, Gray remaining unconfirmed in no way diminishes his significant legal achievements or his stature in the legal community.

[1] Barclay Key, Encyclopedia of Alabama “Fred Gray”, http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1510 (last visited Jan. 14, 2018).

[2] Sheldon Goldman, Picking Federal Judges 266 (Yale University Press 1997).

[3] See Key, supra n.1.

[4] See id.

[5] 364 U.S. 339.

[6] Barclay Key, Encyclopedia of Alabama “Fred Gray”, http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1510 (last visited Jan. 14, 2018).

[7] See id.

[8] See id.

[9] Sheldon Goldman, Picking Federal Judges 266 (Yale University Press 1997).

[10] See id. at 272.

[11] See id.

[12] Id.

[13] Charles R. Babcock, Carter Names Record Number of Minorities to Federal Bench, Wash. Post, May 25, 1980, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1980/05/25/carter-names-record-number-of-minorities-to-federal-bench/bc2babfd-fc49-4101-8d8c-20091a172e8d/?utm_term=.d1259ef428ca.

[14] See id.

[15] J.M. McFadden, U.S. Judgeships in Alabama Add to Carter Headaches, Wash. Post, Feb. 7, 1980, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1980/02/07/us-judgeships-in-alabama-add-to-carter-headaches/23643607-266b-45d5-aac6-0ed4d969c7a5/?utm_term=.49407285225e.

[16] See id.

[17] See id.

[18] See McFadden, supra n.13.

[19] See Babcock, supra n.11.

[20] See id.

[21] See id.

[22] Sheldon Goldman, Picking Federal Judges 267 (Yale University Press 1997).

[23] See id.

[24] See id.

[25] See id.

[26] Barclay Key, Encyclopedia of Alabama “Fred Gray”, http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1510 (last visited Jan. 14, 2018).

Pingback: Civil Rights Attorney Fred D. Gray to be recognized with the Presidential Medal of Freedom on July 7 - Blackamericahealth