Kevin Newsom, President Trump’s first nominee to the Eleventh Circuit, is a seasoned appellate litigator, seemingly universally respected, with extensive experience in diverse areas of law. A longtime member of the Federalist Society, his confirmation would cement the somewhat evenly balanced Eleventh Circuit back onto a firm conservative footing.

Background

Kevin Christopher Newsom, born in 1972,[1] graduated first in his class from Samford University in 1994 before moving on Harvard Law School, where he graduated magna cum laude in 1997 and served on the Harvard Law Review.[2] After law school, Newsom clerked for prominent conservative Judge Diarmuid O’Scannlain on the Ninth Circuit (1997-98). Clerking for O’Scannlain, a “feeder judge” for the Supreme Court, led Newsom to a clerkship with Justice David Souter (2000-01).[3] Newsom described working for Justice Souter—who is not known for his conservative views—as a “dream job,” and characterized his former boss as “blindingly brilliant.”[4]

After clerking for Justice Souter, Newsom stayed in DC doing appellate litigation for Covington & Burlington. He chose Covington & Burlington because he wanted to become a law professor and had heard that the firm had “a strong reputation for sending its alumni into the teaching field.”[5] But he became entranced with appellate law and after two years left the firm to take a position as Alabama’s Solicitor General in 2003.[6] The man who hired him? Then-Alabama Attorney General—now Eleventh Circuit judge—William Pryor.[7]

In 2007, Newsom left the SG gig for Bradley Arant, where he remains as a partner today.[8] Since his start at Bradley Arant, he has at various times served as an adjunct professor at Samford University’s Cumberland School of Law, Vanderbilt University Law School, and the Georgetown University Law Center.[9]

Newsom has been a member of the Federalist Society since 1999.[10] He was President of the Birmingham Lawyers Chapter from 2012-2015, and since 2007 he has regularly presented at Society events and has been a member of the Executive Committee of the Society’s Federalism and Separation of Powers Practice Group.[11] His fellow members on that committee include conservative legal luminaries such as Paul Clement, Greg Katsas, Eleventh Circuit Judge William Pryor, and fellow Trump nominee for the Eighth Circuit and current Minnesota Supreme Court Justice David Stras.[12] Newsom has also been a member of the American Law Institute since 2006.[13] Since 2011, he has served on the U.S. Judicial Conference’s Advisory Committee on Appellate Rules.[14]

History of the Seat

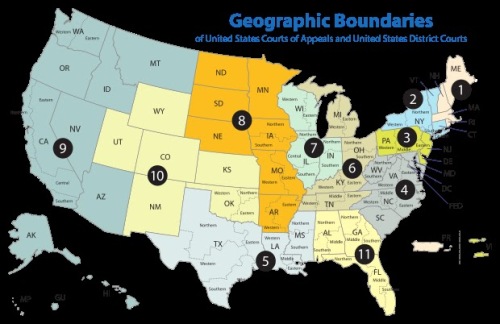

The seat Newsom was tapped for has been open since the retirement of Judge Joel Dubina in 2013.[15] Dubina, the father of Alabama Republican Representative Martha Roby, left the Circuit at a time of significant turnover, with four seats out of twelve open on the court. While the Obama Administration appointed three judges to the Circuit, somewhat moderating its conservative tilt, Alabama Senators Richard Shelby and Jeff Sessions were unable to come to an agreement with the Obama Administration over a nominee for the Dubina vacancy.[16]

More than two years after the vacancy opened, Obama nominated Judge Abdul Kallon to fill the vacancy.[17] While Kallon, a former Bradley Arant partner himself, had been confirmed as a federal district judge with Shelby and Sessions’s support, they refused to return blue slips for his elevation.[18] With no blue slips, the Judiciary Committee took no action on Kallon’s nomination, and the seat was left unfilled during the Obama Administration.

Legal Career

As the Solicitor General for Alabama, Newsom argued many cases and participated in a number of filings before the U.S. Supreme Court.[19] He was the counsel of record in an amicus filing on behalf of 25 states in a case challenging a three-drug lethal-injection protocol, Hill v. McDonough, 547 U.S. 573 (2006). Hill had brought his claim under § 1983, but the Eleventh Circuit held that his § 1983 claim was the functional equivalent of a habeas petition, and because Hill had previously sought federal habeas relief, his new claim was barred as successive under 28 U.S.C. § 2244.[20] In his amicus brief for the various States, Newsom endorsed this view and further made the case that “[e]leventh-hour litigation like Hill’s fatally frustrates” the States’ “ability to carry out duly-adjudicated death sentences in a timely manner.”[21] Permitting “all manner of execution-related challenges to proceed via §1983,” Newsom contended, would come “at the cost of the finality interests that the federal habeas corpus statute is designed to protect.”[22] To illustrate his concerns, Newsom related the story of former Alabama prisoner David Lee Nelson, who—as told by Newsom—manipulated the Supreme Court into granting him continued litigation on his claims.[23] Newsom argued Alabama’s position in Nelson’s appeal,[24] and in Newsom’s view, permitting Hill to challenge the execution protocol under § 1983 would compound the supposed flaw in the Supreme Court’s treatment of Nelson.[25]

In its opinion, the Supreme Court unanimously reversed the Eleventh Circuit.[26] Although the Court stated that “the State and the victims of crime have an important interest in the timely enforcement of a sentence” and that “courts should not tolerate abusive litigation tactics,” the Court unanimously rejected Newsom’s arguments, as well as those by the respondents and the federal government (as amicus), as inconsistent with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the court’s precedent.[27] In Hill’s case, Newsom’s fear about further protracted litigation did not come to fruition. The Supreme Court’s reversing opinion—in which it noted that it was not ruling on the “equities and the merits of Hill’s underlying action”—was handed down on June 12, 2006.[28] Three months later, on September 20, 2006—following several more opinions from the district court and Eleventh Circuit[29]—Hill was executed.[30]

Newsom, again as Alabama’s SG, also defended against a constitutional challenge to Alabama’s statutory ban on the distribution of sex toys.[31] (Disclosure: The ACLU, for whom I work, was opposing counsel in the case.) The Eleventh Circuit, in several opinions (the Williams cases), addressed the question whether the ban could survive Supreme Court precedent—including, ultimately, Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003)—holding that it did.[32] Newsom’s position, accepted by the court, was—in the court’s words—that “public morality remains a legitimate rational basis for the challenged legislation even after Lawrence.”[33] A decade later, however, the Eleventh Circuit has granted rehearing en banc in another case on the question whether one of the Williams cases is still good law and whether a Georgia municipality’s ban on the sale of sex toys is constitutional.[34] Although the specific Williams case in question is not the one in which Newsom was counsel, the broader constitutional inquiry that the court will address directly implicates the case in which he was involved as well.[35] Oral argument in that case will be held on June 6, 2017.[36]

Finally, Newsom also argued for Alabama in a case concerning preclearance under the Voting Rights Act, Riley v. Kennedy, 553 U.S. 406 (2008). There, Alabama—a “covered” jurisdiction under the VRA, meaning it must obtain “preclearance” from the U.S. DOJ before changing voting procedures—sought to reinstate a prior voting practice following the Alabama Supreme Court’s conclusion that a newer practice was unconstitutional.[37] Newsom successfully contended that Alabama’s return to its prior practice did not qualify as a change requiring preclearance—Justice Ginsburg wrote the 7-2 opinion in Alabama’s favor.[38] Justice Stevens, along with Newsom’s former boss, Justice Souter, dissented.[39]

Writings

Newsom has received some scholarly attention for an article he published in the Yale Law Journal while working as an associate at Covington & Burling: “Setting Incorporationism Straight: A Reinterpretation of the Slaughter-House Cases.”[40] In that article, which he developed while serving as a research assistant on Professor Laurence Tribe’s constitutional law treatise,[41] Newsom takes on the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause, arguing that the conventional scholarly interpretation of the Slaughter-House Cases is mistaken. While many commentators believe the Clause incorporates most or all of the protections of the Bill of Rights against the states and that the Slaughter-House Cases were therefore wrongly decided, Newsom agrees with former and disagrees with the latter, instead arguing that the Cases are consistent with an incorporationist interpretation of the Clause.

In reaching this conclusion, Newsom offers his views on the doctrine of substantive due process, stating that his interpretation “would permit courts to lay aside the historically confused and semantically untenable doctrine of ‘substantive due process,’ a doctrine that has for years visited suspicion and disrepute on the judiciary’s attempt to protect even textually specified constitutional freedoms, such as those set out in the Bill of Rights, against state interference.” Although he states that his primary concern about what his interpretation of Slaughter-House means for substantive-due-process doctrine is the protection of “substantive Bill of Rights freedoms” (such as the freedom of speech), purportedly leaving “for another day” what his reinterpretation means for the “more controversial branch of substantive due process”—“the protection of unenumerated rights against state interference”—he nevertheless makes plain those views as well: (1) substantive due process is inconsistent with the constitutional text; (2) it is inconsistent with the intent of the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment; (3) because of those reasons, reliance on the doctrine undermines the integrity of the Supreme Court and the “institution of judicial review”; and (4) the doctrine can be traced to the Dred Scott decision and therefore suffers a “pedigree” problem. On this latter point, Newsom offers his advice to judges: “courts invoking substantive due process—the idea of grounding protection for a substantive right in what is, by all accounts, a purely procedural provision—would do well to remember that all roads lead first to Roe, then on to Lochner, and ultimately to Dred Scott.” Presumably, this statement is intended to suggest that all three decisions—not simply Dred Scott and Lochner, but also Roe—were wrongly decided.

Newsom’s views on substantive due process put him at odds with current Supreme Court caselaw—which obviously recognizes the existence of substantive-due-process doctrine—but it does not place him out of the conservative mainstream, which has long challenged Roe in particular and substantive due process more generally. Notably, his potential future colleague on the Eleventh Circuit—should Newsom be confirmed—is Judge William Pryor, who called Roe the “worst abomination in the history of constitutional law.”[42] (Judge Pryor was initially filibustered by Senate Democrats and was installed as a circuit-court judge by President George W. Bush through a recess appointment.[43]) Newson’s apparent wholesale rejection of substantive due process is also shared by at least one member of the current U.S. Supreme Court—Justice Clarence Thomas. Justice Thomas was confirmed in 1991 by a narrow margin and in a confirmation environment that was much more forgiving than today’s. Given the change in environment and Justice Thomas’s willingness to overturn otherwise settled law in a variety of areas “in an appropriate case”[44]—including in the area of substantive due process[45]—it is not clear that he could be reconfirmed today. What this means with someone of Newsom’s specific views on substantive due process is unclear, but given that Newsom is not being nominated for the Supreme Court but for the Eleventh Circuit, he would not be in a position—for the moment, at least—to overturn Supreme Court caselaw in that or in any other area. At most, he will be in a position to narrowly interpret or distinguish such cases. This is true of any other judge on the court, but it is not insignificant, particularly given his assertion that “courts invoking substantive due process … would do well to remember that all roads lead first to Roe….” This advice was not directed solely at the Supreme Court but rather courts, plural—presumably including the court to which he has been nominated. The statement seems to suggest that all courts should consider the putative illegitimacy of Roe when addressing claims involving the doctrine of substantive due process.

Such a statement is at odds with Supreme Court precedent, which not only reaffirmed Roe in 1992 (Casey[46]) but relied on it as recently as 2016 (Whole Woman’s Health[47]). Perhaps this interpretation of Newsom’s writing accurately reflects his views as a recent law school graduate, but there does not appear to be any publicly available indication that he would in bad faith resist the application of Supreme Court caselaw with which he disagrees. When I asked former Alabama Solicitor General John Neiman for his own view on Newsom’s nomination, he replied, “[h]e is a great pick and extremely qualified.”

Overall Assessment

On paper, Kevin Newsom is an eminently qualified nominee for the Eleventh Circuit. His views on substantive due process, however, while not out of step in the community of conservative legal superstars through which he moves, are inconsistent with current caselaw, and his apparent views on Roe in particular could draw significant concern from some quarters. Nevertheless, I believe that Newsom is a highly qualified pick for the President.

[1] Kevin Newsom, Questionnaire for Judicial Nominees at 1, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Newsom%20SJQ.pdf.

[7] http://www.dailyreportonline.com/home/id=1202785561620/Bradley-Arant-Partner-Kevin-Newsom-Said-to-Be-on-Tap-for-Eleventh-Circuit?mcode=1202617074542&curindex=1.

[8] http://www.dailyreportonline.com/home/id=1202785561620/Bradley-Arant-Partner-Kevin-Newsom-Said-to-Be-on-Tap-for-Eleventh-Circuit?mcode=1202617074542&curindex=1.

[9] Kevin Newsom, Questionnaire for Judicial Nominees at 2, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Newsom%20SJQ.pdf.

[10] Kevin Newsom, Questionnaire for Judicial Nominees at 6, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Newsom%20SJQ.pdf.

[11] Id.

[12] http://www.fed-soc.org/practice_groups/page/federalism-and-separation-of-powers-practice-group-executive-committee-contact-information.

[13] Kevin Newsom, Questionnaire for Judicial Nominees at 6, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Newsom%20SJQ.pdf.

[14] Kevin Newsom, Questionnaire for Judicial Nominees at 4, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Newsom%20SJQ.pdf.

[15] Dottie Perry, Exodus from 11th Circuit Presents a Ripe Opportunity…That Will Likely Rot, The Legal Examiner Mobile, Aug. 26, 2013, http://mobile.legalexaminer.com/miscellaneous/exodus-from-11th-circuit-presents-a-ripe-opportunity-that-will-likely-rot/.

[16] Mary Troyan, Shelby Blames White House for Lack of Judges, Montgomery Adviser, Sept. 21, 2015, http://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/2015/09/22/shelby-blames-white-house-lack-judges/72604440/.

[17] Mary Troyan, Obama Appoints Judge Abdul Kallon to 11th Circuit, Montgomery Adviser, Feb. 11, 2016, http://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/news/2016/02/11/obama-appoints-judge-abdul-kallon-11th-circuit/80253358/.

[18] Id.

[19] Kevin Newsom, Questionnaire for Judicial Nominees at 26-28, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Newsom%20SJQ.pdf.

[20] Hill v. McDonough, 547 U.S. 573, 576 (2006).

[21] Amicus Brief at 1, https://www.clearinghouse.net/chDocs/public/CJ-FL-0002-0012.pdf.

[22] Amicus Brief at 4, https://www.clearinghouse.net/chDocs/public/CJ-FL-0002-0012.pdf.

[23] Amicus Brief at 4-7, https://www.clearinghouse.net/chDocs/public/CJ-FL-0002-0012.pdf.

[24] See Nelson v. Campbell, 541 U.S. 637 (2004).

[25] See Amicus Brief at 14-16, https://www.clearinghouse.net/chDocs/public/CJ-FL-0002-0012.pdf.

[26] Hill v. McDonough, 547 U.S. 573 (2006).

[27] Id. at 582-83.

[28] Id. at 585.

[29] Hill v. McDonough, 462 F.3d 1313 (11th Cir. 2006); Hill v. McDonough, No. 4:06-CV-032-SPM, 2006 WL 2556938 (N.D. Fla. Sept. 1, 2006); Hill v. McDonough, No. 4:06-CV-032-SPM, 2006 WL 2598002 (N.D. Fla. Sept. 11, 2006); Hill v. McDonough, 464 F.3d 1256 (11th Cir. 2006); see also Hill v. McDonough, 548 U.S. 940 (2006).

[30] Florida prisoner executed after court rejects cruelty claim, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/sep/21/usa.edpilkington.

[31] Williams v. Morgan, 478 F.3d 1316 (11th Cir. 2007).

[32] See id. at 1318-19; see also Williams v. Attorney Gen. of Ala., 378 F.3d 1232 (11th Cir. 2004).

[33] Williams v. Morgan, 478 F.3d 1316, 1318 (11th Cir. 2007).

[35] See id.

[36] Id.

[37] See Riley v. Kennedy, 553 U.S. 406, 411-12 (2008).

[38] Id. at 411, 421-22.

[39] Id. at 429.

[40] Kevin Christopher Newsom, Setting Incorporationism Straight: A Reinterpretation of the Slaughter-House Cases, 109 Yale L.J. 643 (2000).

[41] Bryan H. Wildenthal, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Slaughter-House Cases: An Essay in Constitutional-Historical Revisionism, 23 T. Jefferson L. Rev. 241, 244 n.11 (2001).

[44] E.g., Shepard v. United States, 544 U.S. 13, 28 (2005) (Thomas, J., concurring).

[45] E.g., McDonald v. City of Chicago, Ill., 561 U.S. 742, 811-13 (2010) (Thomas, J., concurring in part and concurring in the judgment).

[46] Planned Parenthood of Se. Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

[47] Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, 136 S. Ct. 2292 (2016).

It seems thorough and measured. Regarding Justice Thomas’ feeble but dispositive support in the Senate at the time of his appointment, it may not have been “on the merits”, but no doubt it was influenced by the Anita Hill controversy.

LikeLike

Pingback: Thoughts on Today’s Judiciary Committee Hearing | The Vetting Room

Pingback: The Age Question | The Vetting Room

Pingback: Four Nominees Advance to Senate Floor | The Vetting Room

Pingback: Trump’s Latest Judicial Picks Continue to be Terrible for Abortion Rights | Abortion - Abortion Clinics, Abortion Pill, Abortion Information

Pingback: Anna Manasco – Nominee to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama | The Vetting Room

Pingback: Judicial Nominations 2021 – Year in Review | The Vetting Room